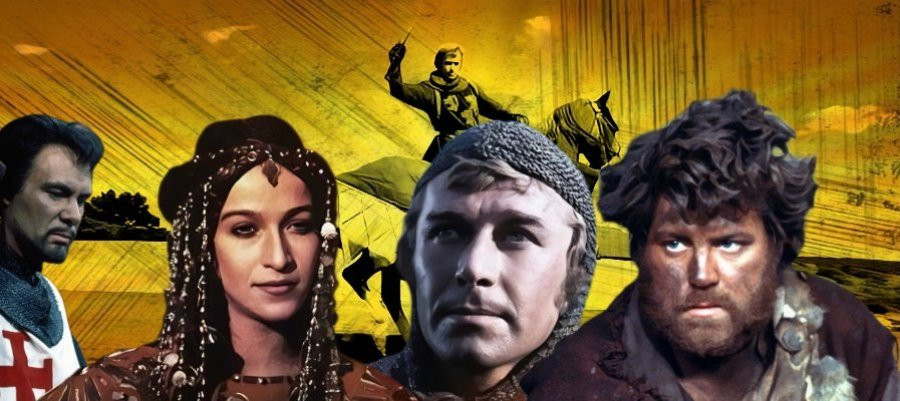

The Best of... Arthur of the Britons – The Challenge

Chosen by John Winterson Richards

That there was a wide variation in the quality of its 24 episodes might explain why Arthur of the Britons never really achieved the huge commercial success and classic status it deserves. It is nevertheless remembered very fondly by those, including the author of this article, who loved it back in the Seventies.

Rewatching it today, the most surprising thing about it is that it was seen as a children's show, or at least a family show, at the time, because it is very dark in both story and tone - as dark as the so-called Dark Ages in which it is set. In the Fifth Century AD, the Roman Emperor, with Barbarian invaders on his own doorstep, told his subjects in the distant provinces of Britannia that he could not spare troops to protect them, and they would have to fend for themselves. They were completely unprepared for this. The result was a complete collapse of law and order, and then, as a result, of the economy. In the absence of trade to support them, cities and towns shrank to villages, and civilisation reverted to the clan system. These smaller communities became easy prey for invaders from all sides - Picts from what is today Scotland, Scots (confusingly) from Ireland, Saxons from Germany, Jutes from Jutland in Denmark, and Angles, apparently from the angle between Germany and Jutland. When the Romano-Celts who became the Britons were not fighting these invaders they were fighting each other.

All were, at the best of times, living only slightly above subsistence level, so the struggle for land and resources was literally a fight for survival. It was merciless and brutal, starvation, slavery, or genocide being the price of defeat, as this "children's show" makes very clear. The Britons survived only because leaders eventually arose among them with the strength and vision to unite the different clans and communities against the common foe. At least one of them really was called Arthur.

This Arthur, conflated with other historical figures, leant his name to much later Medieval legends and romances. What Arthur of the Britons tries to do is imagine the real man behind the myths. The leader of a warband, possibly little more than a gangster himself, being paid for "protection" by the villages under his control, he lives in muddy squalor, hunting for his own food. Yet unlike most of his kind, he has dreams of something better for the people he leads.

While Arthur of the Britons therefore aspires to present a more "realistic" Arthur, it is debatable how accurate it is because we still know very little about Sixth Century Britain. Possible sources in Welsh Abbeys were destroyed, sometimes deliberately, by Anglo-Norman invaders, and, until recently, archaeologists tended to dive straight down to the solid and more glamorous level of Roman remains, paying little attention just above them. If anything, Arthur of the Britons probably downplays the enduring Roman influence to suggest a greater reversion to pre-Roman Celtic culture than was probably the case. This notion was already fashionable in modern literary reconstructions of Arthur by the 1970s.

It was also particularly popular in Wales, home of at least one of the original Arthurs and part of the region served by the Wales and the West ITV franchise held by HTV (Harlech Television). HTV were always keen to punch above their weight as a regional franchise, and they found the ideal combination of a big dreamer and a practical executive in Patrick Dromgoole, an ambitious Bristol-based producer with an eye for history and international sales who was to rise to become Chairman of the company. He was responsible for a long chain of excellent HTV historical dramas, many of them co-productions, that sold well abroad, including Pretenders, Kidnapped, The Master of Ballantrae, Robin of Sherwood, and Return to Treasure Island.

As one of his earlier projects, Arthur of the Britons, was clearly not as expensive as some of his later co-productions with major American corporations. There are no big name stars among the principals and the number of extras is often limited, even in big set piece battles. Although it should be said that it also must have had a substantial budget (not least for Elmer Bernstein, of The Great Escape fame, writing the memorable orchestral theme), and therefore fairly good production values, by the standards of British regional television of the time, those standards now look rather quaint. This is not mocking Dromgoole and his team, who were very skilled at making a lot out of a little. On the contrary, one can only wonder what they might have achieved had they access to the sort of CGI used in the similarly themed Vikings several decades later.

Indeed, it is partly as a tribute to HTV's talent for getting value for money that The Challenge is the episode I have chosen to illustrate the best of Arthur of the Britons." It was not an easy choice. It was hard to set aside the claims of both the very first episode and the very last of its two seasons - the former being admirable for having the courage to jump right in at the apparent end of the story with the minimum of exposition, the latter for its beautiful photography of a completely out of place but always welcome Catherine Schell as an ahistorical Roman "Princess." It is also a matter of regret that The Challenge is not one of the episodes which guest starred Rupert Davies as Cerdic the Saxon, Clive Revill as Rolf the Preacher, or Brian Blessed, when he was at absolute peak Brian Blessed, as King Mark of Cornwall.

The whole cast of The Challenge consists of only five actors, the three regular principals - Oliver Tobias as Arthur, Michael Gothard as his Saxon foster brother Kai, and Jack Watson as their foster father Llud of the Silver Hand - and two guest stars familiar from numerous projects around that time, Nicky Henson (Witchfinder General, Psychomania) and Ken Hutchison (Masada, Ladyhawke), plus their five horses.

There are none of the usual village sets and the only props are weapons, even if it should be noted that Arthur's poor horse seems to be carrying more of these than usual, a mobile armoury in fact - this is a clue to what follows. It therefore looks like one of the cheaper episodes, taking the pressure off the budget for others that required more extras, sets, and props, except a more experienced eye might notice that it is filmed entirely on location and uses a huge number of set ups in the action scenes, so perhaps it was not so cheap after all.

The story was written by Terence Feely, one of the great names of the Golden Age of British television drama writing (read our review of Number 10 and his biography on this website for more about him - he really ought to be better known). He wrote more episodes of Arthur of the Britons than anyone else, and there might have been more consistency to the show if he had written them all.

In The Challenge he gives us a masterclass of how much can be packed into just 25 minutes. There is a strong central story arc with a beginning, a middle, and an end. Within this each of the five characters has his own distinct character arc, even if the two guest stars basically have the same one. Each changes in some way as the story progresses as a result of what is happening. The dialogue is sparse, no words being wasted. When the characters speak, what they say means something. Yet there is also room for a little grim humour as Arthur and Kai exchange what seem, at first, to be no more than friendly insults.

There is, however, a lot of subtext to all this. As the show often did, the episode touches briskly on some big themes - in this case family, friendship, leadership, and what it means to be a man and a warrior.

In the backstory to the show, Arthur and Kai - the "Sir Kay" of the Medieval romances - were trained by the tough old warrior Llud, as he says, to fight battles, not play games. All three are therefore serious men, their emotions suppressed. This has left the sibling rivalry between Arthur and Kai unresolved. It does not help that Arthur feels the burden of being destined to lead his people while Cai, born a Saxon, sometimes feels a bit of an outsider. These themes reoccur in different forms in other episodes. Here Arthur lets the childish side that he has had to suppress take over from the leader for a little while and Kai's Saxon side begins to assert itself more. Yet it is at the same time something far more basic and universal: pure biology as two healthy, powerful young males clashing because both are eager to assert their dominance.

It is a fascinating study in psychology and the only criticism is that it came too soon in the first season: The Challenge was the third episode to be broadcast and it would undoubtedly have had far more impact if the audience had been given more time to get to know the characters before the tension that always seems to be just below the surface throughout the two seasons was released so dramatically.

Pitched Battle - a closer look at the episode’s dramatic fight scene:

The episode begins with two of Arthur's vassals, Gawain and Garet, named after two brothers popular in the Medieval romances, Sir Gawain and Sir Gareth, but cousins here, duelling as part of a long running family feud in accordance with established Celtic tradition. They are arrested by Arthur, Kai, and Llud. As they are being escorted into exile, they attempt to escape in different directions.

Arthur and Kai pursue them separately, having made a friendly wager who will catch his man first. This is the beginning of a series of contests between the two foster brothers that become less and less friendly as one provokes the next.

The second is a spear throwing context for distance and the third one for accuracy. This leads to them throwing spears at each other, covering their points with sheepskins and using their shields to deflect them. Then they get back on their horses for full on jousting. This leads in turn to an increasingly violent fight, still on horseback, between Arthur's sword and Kai's battle axe, still deflecting blows with their shields - except they continue even when their shields are shattered and then when both are dismounted. When one of them is disarmed, they continue with Roman short swords - killing weapons and nothing else. Finally, they wrestle in the mud until one of them finds Kai's axe and the other draws a dagger. By this point they both look like men seriously trying to kill each other.

It is a long sequence, over twelve minutes, about half of the episode, of constant conflict in ten different forms. They become more and more aggressive, a reflection of the increasingly open hostility in the tone, expressions, and actions of the two characters. There was always a distinct edginess between them throughout the show's run. Here it grows and grows until it explodes.

It is just as interesting to watch Llud's reaction to all this. The experienced older man understands exactly what is happening and where it is likely to lead, so he twice tries to stop the conflict before it gets out of hand. Arthur brushes him off, telling him it is only a game - but it is already clear that it is nothing of the sort, and Llud has already said that he trained both Arthur and Kai for war not for games. Yet as the violence reaches its height, Llud accepts that this was something that had to happen, even if he fears that if one kills the other it will be the death of both of them.

This is all very subtle stuff for a 25 minute "children's" show.

Of course, speaking as one of those children at the time, it was the action, not the psychological nuances, that kept me glued to the screen when I first saw it, and helped cement this episode more than any other into my memory for many years until I bought the DVD about three decades later.

Director Sidney Hayers, who directed more episodes of Arthur of the Britons than anyone else and went on to a very successful career directing episodes of many different shows, usually associated with action, and fight arranger Peter Brayham, also near the start of a very distinguished career, use the episode as a showcase for their technical skills. The fights are wholly believable, even if a purist might complain the Roman short swords and the technique with which they are used here are not entirely accurate.

However, it is Tobias and Gothard who really sell both the violence and what leads up to it. Both men look as if they really want to have a go at each other.

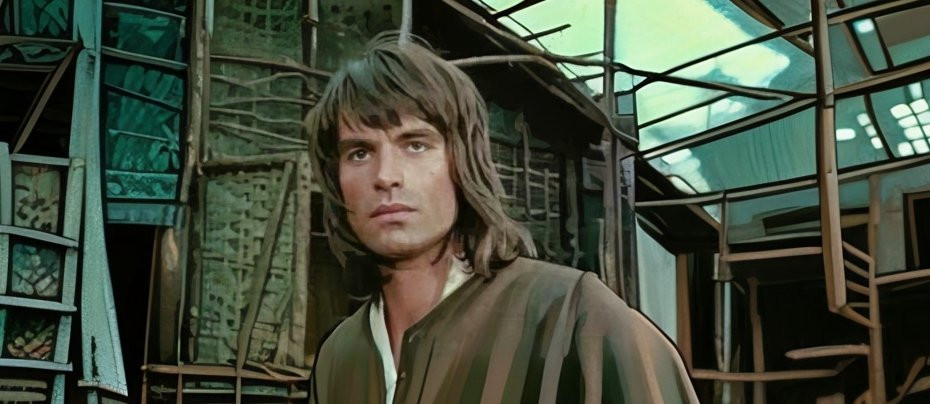

Both were noted as physical actors. It was quite common at that time for actors to be trained in fencing. Whether or not Tobias and Gothard completed formal courses as part of their own training, there is no denying that both look natural and comfortable handling weapons, and also on horseback. Tobias had come to prominence as a stage actor. His breakthrough had been as the passive-aggressive hippie Berger in the musical Hair. He brought that same sense of latent danger to the role of Arthur. In a subsequent episode he performs a clever trick kicking a sword up into his hand - he could actually do it in real life: I saw him perform a slight variation, kicking a sword accurately to another actor, live on stage in The Pirates of Penzance a few years later. Gothard was also an actor known for his physical commitment to his roles.

Both were seen very much as coming men at the time. I remember Tobias described in the late Seventies as being at the head of the queue to replace Roger Moore when he finally quit as James Bond. Sadly, Moore kept being persuaded to do just one more and hung on too long. This is doubly a pity because it would have been fascinating to see what Tobias made of the role. As it is, his subsequent career probably suffered from a couple of poor film choices. Gothard did better in film roles, including making it into Bond as a memorable villain, but not as a leading man. He died tragically at the young age of 53.

So it turns out that in Arthur of the Britons we are watching both actors in what turned out to be their prime. Perhaps the clash of two aspiring alpha males in The Challenge is convincing because that is what Tobias and Gothard were in real life at that point. The episode is charged unapologetically with testosterone and raw masculinity. The same is true of the show in general, but it is released from all restraint in this episode more than any other.

Of course, as a child, I appreciated none of this. I just knew I wanted to be like Arthur and Kai and Llud, and I copied the fighting moves I saw in The Challenge in my own childhood games for some time after. In retrospect, they are perhaps not the best role models a boy could have had, but there are many worse on television today, and they certainly stuck in the mind - and still do.

Published on September 11th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.