The Big Routine: Jack Webb’s Dragnet

‘The story you are about to hear is true. The names have been changed to protect the innocent.’

review by Nur Soliman

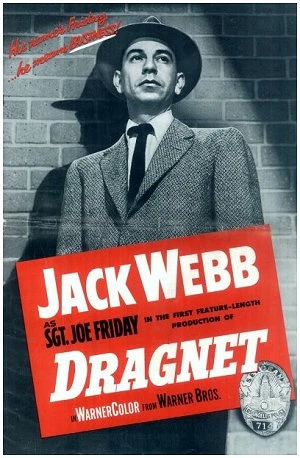

Reflecting on Jack Webb’s Dragnet can seem like a master study of adaptation. From 1949 on, iterations of the police series made their mark on audiences, with iconic recurring elements like the ominous musical opening theme, Sgt. Joe Friday’s matter-of-fact scene-setting introductions, and the unnerving mug-shot closing sequences. Dragnet became the ship that launched a thousand radio/TV ‘procedurals’ flooding the airwaves and permeating our cultural consciousness since.

Today, it can appear dull, dated, even unintentionally self-parodying, as the progressive Webb began to sound jarringly staid and conservative in a changing, conflicted era. If the format feels over-familiar it’s likely because it was the first of its kind, but in a way Dragnet itself was conceived as an adaptation, after Webb befriended and spoke with Marty Wynn of the LAPD while filming that classic crime/police procedural noir He Walked by Night (1948). Webb found that even real-life ‘dullness’ had meaningful, storytelling potential and adopted a factual approach for his series; what he eventually produced became its own creature entirely.

The original franchise included two tele-film adaptations. Disappointingly, they didn’t bring the successful film break Webb hoped for (what he ran with eventually ran away with him: the 1967 film reportedly got him to make the second TV series, beginning to tire the legendarily intense workhorse), and he only directed a handful of other (good) films before turning out popular series like Adam-12 and Emergency! but I feel the Dragnet films allow us to enjoy Jack Webb at his almost-finest. They’re imperfect and fall a little short, but they’re also promising glimpses of what he might have been capable of with a little more experimentation, still fine complements to the old radio/TV episodes extant today.

Dragnet (1954)

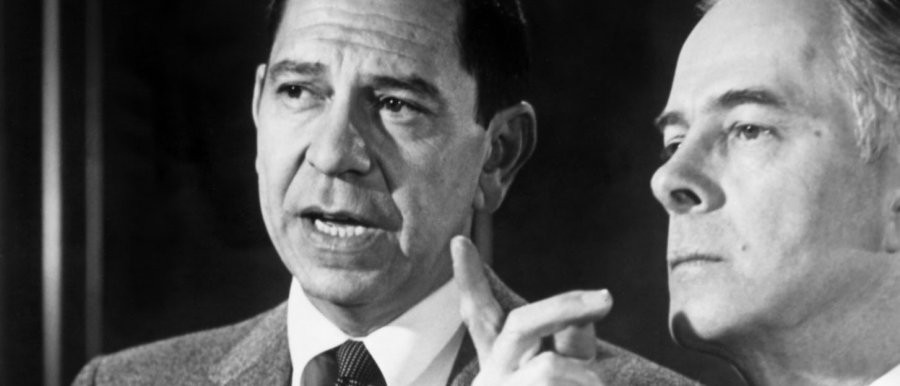

This film feature (the first-ever theatrical film based on a television series) is essentially an extended TV episode, with Friday (Webb) and partner Frank Smith (Ben Alexander) investigating the gangland murder of a small-time bookie and ex-con. The Department has their eye on all the right hoodlums but are hard-pressed for substantial proof that would hold up for an indictment. The pressure builds up to breaking point between the detectives and their suspects who elude them at every turn. Plucky policewoman Grace Downey (Ann Robinson) finally obtains vital incriminating evidence, but is it too late?

It’s a treat to see the series’ hallmarks transferred as-is in higher production value and glorious colour, from the quick hardboiled dialogue and matching, alternating close-ups, to the obsessively linear book-procedure. The film also presents some interesting departures from Webb’s usual formula. There’s more in-depth exploration of plot akin to ‘30s/’40s crime films and novels. The ever-changing gallery of criminals, victims, and officers were usually drawn with some economy against the larger landscape of the weekly crime and Webb’s beloved Los Angeles, which isn’t actually the shortcoming it sounds like it is. Actors were usually discouraged from memorising their scripts (reading from cue-cards/TelePrompTers), which strangely enough results in restrained but realistic-feeling exchanges. But here we get to enjoy a little more from Webb’s stock casts and go-to favourites, consistently distinguishable by their voices as well as faces. There are longer, lingering scenes with chief suspect Max Troy (whose delicate stomach condition might be borrowed from infamous mobster Mickey Cohen), superbly played by Stacy Harris, and stalwart character actor Virginia Gregg has a touching, inspired cameo as the victim’s widow drowning her grief in drink – even the blank-slate straight-backed Friday reveals a new, uncharacteristically physical, side to his nature.

Webb also stretches his directorial wings with well-rewarded risk, venturing into new visual territory, with interesting plays on light, angles, and camera motion worth admiring, trademarks of a man who flourished finding his space in any medium. Other parts of the film don’t hold up as well: the heavy-handed musical cues and schmaltzy archness are palatable, even endearing, in the half-hour segments; here they can seem comically over-serious. Most importantly, after a violently effective ‘howcatchem’ opening, the story slightly peters out, with more time than it knows how to occupy fully, saved by the ever-reliable structure covering all the avenues the force would have to diligently pursue. The film still sits very comfortably in the Dragnet universe though, a fascinating lens into the Webb world-view which means these pacing weaknesses are generally overlooked by the loyal viewer: it would just take more film-length features for Webb to tell a better film-length story.

The Big Dragnet (1967)

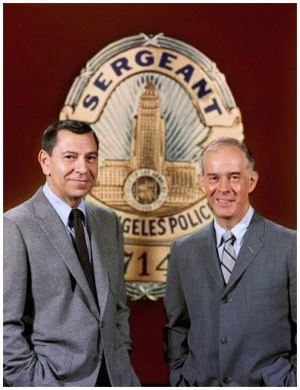

After ending the first television series, Webb may have hoped to return to the world of Dragnet in the form of occasional tele-films, but this second outing would end up slightly revised and embedded within the ‘60s TV series. Dragnet never shied away from tough themes, but this film has a particularly dark, lurid crime, as Friday and new partner Officer Bill Gannon (a pre-M*A*S*H Harry Morgan) painstakingly trace the fate of four missing women who fall victim to a depraved ‘Lonely Hearts’ killer (also mostly based on a real-life case). The detectives seem to go in circles for a while, thoroughly sorting through conflicting descriptions, conscientiously pursuing clues and leads that go nowhere, even solving another unfortunate murder on the way, before the trail culminates in a confrontation. This stand-off, between scads of squad cars and an unstable trailer on a muddy precipice (in a rainstorm at night, no less), is perhaps one of Webb’s greatest dramatic scenes across Dragnet, but the key of the case would still come afterwards, just part of regular routine.

Here too, familiar faces, guiding voice-over, linear structure, brisk dialogue and close-ups, plus the sometimes-sentimental sombreness and drab celadon-green interiors that would feature more often in the ‘60s series. But this film feels a lot more like a feature: the trademarks are still there but they become a secondary framework for creative, artistically engaging direction, richer character-focused moments, accommodating more atmosphere, suspense, mystery, even action over the clipped-pace accuracy that Dragnet typically relied on. There’s even humour, one of the great saving graces of the film (and the ensuing series), and it’s all down to Morgan.

Ever since the show got its start on radio, Sgt. Friday’s partners like Romero and Smith provided much-needed human warmth and gentle comic relief to the grimness of Dragnet. They were usually kindly married or family men, gentle hypochondriac types with mild, endearing quirks who took a brotherly interest in looking out for Friday who was by contrast a serious altar-boy bachelor with virtually no real personal traits or private life to speak of. If the cool, laconic Friday hardly found anything to smile at in his daily battle against the onslaught of urban crime, there was always something about tonic salt water, odd lunch combinations, or family advice that he could at least wearily humour, moments that would betray Friday’s soft vulnerable heart. The disarmingly good-natured presence of Morgan’s Gannon did this often (starting in this film with ill-fitting dentures and ulcers that are eventually cured by Pismo clams of all things) – and good thing too, considering Friday would grow even more cynical with the way of the world as the series went on.

‘It wasn’t brilliant detection, just routine work.’

These words aren’t from Dragnet but Fabian of the Yard, a 1954 British TV series dramatising cases of the real-life Detective Superintendent Robert Fabian (who closes an episode with this endearingly humble reassurance). Dragnet was so ground-breaking and distinctive in its approach that it influenced Fabian as well as Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct, NYPD Blue, Law & Order, John Creasey’s Gideon’s Way, even certain Western serials and WWII hero anthologies, so far-reaching and natural-seeming is its impact that it survives mostly in imitations.

If it started out as such a glowing innovation however, the last main reincarnation in 1967 would sometimes feel alternately anachronistic, pedantic, or defensive. Elsewhere, TV entertainment was introducing more nuanced irony, camp self-awareness: maximalist, embellished theatres of character and colour. Not so Dragnet, as serious as the post-Depression, post-war noirs it came from, Webb still carrying all the same lessons in economy and conventions in storytelling he adopted as a younger man. With solid scripts that in true B-movie style showed and didn’t tell (even the dialogue showed more than it told), he relied on the same quotidian foundation from which his pageant on humanity emerged, doggedly devoted to portraying the men and women he believed lived to protect others.

His creative strength was perhaps eclipsed by his more old-fashioned sensibilities as well as his ongoing struggles within the network system and industry as a whole, but I’d argue that Jack Webb’s visions makes him one of the greatest, earliest auteurs comparable to better-remembered/stronger successes like Sterling or Spelling. Now perhaps an under-sung, ‘underplaying’ pioneer, Webb left behind an individual, resonant oeuvre, a media legacy as complex as its creator: a man who looked at ‘brilliance’ and ‘routine,’ and found he could make radio/TV alchemy with a little of both.

Published on December 4th, 2022. Written by Nur Soliman for Television Heaven.