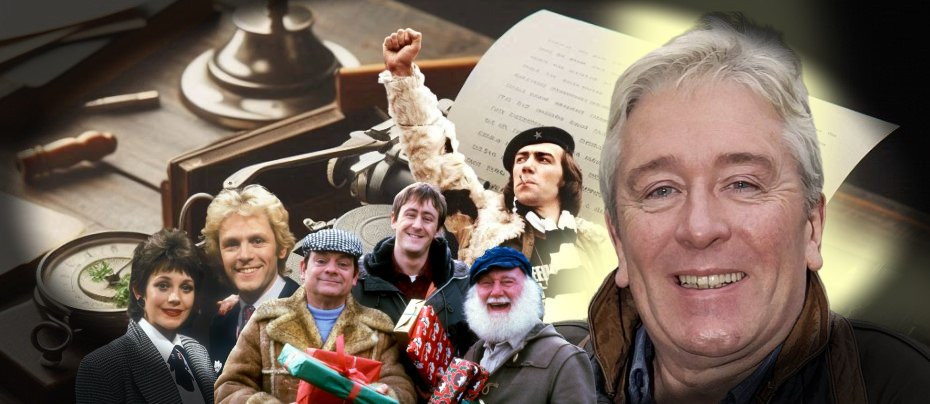

Barry Gray

Biography by Peter Henshuls

An often underappreciated yet vital component to the success and memory of any TV series or film is its music. In the field of classic British telefantasy there has arguably been no finer exponent of this important art form than the man who consistently brought musical life to the iconic stable of Gerry Anderson's Supermarionation universe. That man was the late and much-lamented Barry Gray.

Himself the offspring of musical parents, Barry Gray was born in Lancashire, receiving a sound musical education. Almost from the outset, the young Gray's natural ability was evident enough to cause his first teacher to remark of his arranging and notational abilities: "This young lad takes to manuscript paper like a duck takes to water!"

From this promising beginning Gray went on to study at the Royal Manchester College of Music followed closely by a time spent at Blackburn Cathedral where he learned harmony and counterpoint before progressing to study composition with the eminent Hungarian teacher Matyas Sieber.

After graduating from his studies, Gray's first steady professional job was with Feldman's music publishers in London, where he gained much valuable first-hand experience scoring for many different combinations for theatre, variety and orchestras of varying sizes. Later, he became composer-arranger at Radio Normandy at their commercial radio station in Portland Place where he was destined to remain until the outbreak of World War II.

Following six years of service with the RAF, in locations as diverse as Africa, India and Burma, he eventually returned to London where he embarked upon a career as a freelance composer writing for publishers and films at the Denham Studios. It was also at this time that he began to write a large volume of special material, compositions and orchestrations for numerous BBC shows including the Terry-Thomas radio series, To Town with Terry. Simultaneously he was also scoring for a variety of artists including Eartha Kitt and the legendary Hoagy Carmichael. In 1949 he was engaged to work with former Forces Sweetheart, and future Dame, Vera Lynn as accompanist/arranger scoring her arrangements for the stage, Decca recording sessions and radio and TV shows over the course of the next decade.

1956 saw Gray become Musical Director for a small production company named AP Films Ltd - later to become immortalised as Century 21 Productions - It was to be beginning of a staggeringly successful 18-year association with an imaginative young writer/producer named Gerry Anderson.

Gray's association with Anderson initially came about due to author Roberta Leigh, who had previously known of Gray through Vera Lynn, who had several of Leigh's children's songs. So, when Leigh brought her character Twizzle, to Gerry Anderson, she stipulated that Gray be brought on board as musical director rather than composer. The reason Leigh did not want Gray to be the composer was simply because she had a friend, who was not a musician, who hummed tunes into a tape recorder and it was these that she wanted Gray to arrange for use as the music for The Adventures of Twizzle . With this in mind, Leigh brought Gerry Anderson to Gray's house in London to meet him and discuss her musical ideas for the show. This first encounter between the two men would quickly lead to them becoming professionally inseparable.

Aware of the original simple hummings of Leigh's friend from the tapes, Anderson was tremendously impressed when he attended the recording session at Elstree Studios and heard how Gray had transformed those simple hums into beautifully realised, fully orchestrated music.

In an interview given towards the end of his life, Gray explained his view of the vital role of music as an element of TV and film: "I think, basically, it revolves around impressionism. Impressionism, of course, gives an impression of certain aspects of life, certain situations, certain moods, etcetera. I think the music in a film should really cover this and create the right atmosphere and add to the film's situations. In other words, the visual will be better with the correct type of music than it would be without." The success of The Adventures of Twizzle led the two men almost directly on to their next collaboration, which was also created by Roberta Leigh, Torchy the Battery Boy .

For this show, Leigh sang her own tunes into the tape recorder that were once again memorably orchestrated by Gray into the final themes. It was also at this time that Gray began to set up his own recording studio in London which he founded in 1950 and which specialized in electronics and experimental effects, a subject which coincidentally, also greatly interested Anderson. The studio also saw much use for the composition of incidental music for commercials as well as further work for the BBC and for Vera Lynn, all of which, including tours to Europe with Lynn plus the Anderson/Leigh shows, kept Gray highly busy.

Following the end of the two Leigh/Anderson series, Gray worked on a special musical series featuring the BBC Orchestra. The musical director for this show was highly keen to do special material within the orchestra that would be aimed to appeal specifically to children. To that end Gray conceived a creature called Dumpy, a magical little character who would take himself to any part of the world and describe it to the viewer as the orchestra played the traditional music of that particular region. Asked in a later interview if his approach to composing was different when aimed at children rather than adults, Gray responded: "In the very early days of the Anderson shows it was Gerry's idea not to write kiddie music for the puppet shows and I should not let the fact that the show's stars were puppets affect the music at all. I should write as one would for a film, in the normal way, and this is what I always did. I never wrote down to children. I scored as I felt, or in other words, I treated the puppets as if they were real people. And that was what we did more or less throughout."

Even as Gray was immersed in the project, Gerry Anderson had conceived his latest idea for a children's puppet show, a light-hearted Western series with more than a touch of magic about it. Aware of Gray's involvement with the BBC series, Anderson approached him to write the script for the first episode of the new series. Gray agreed, and eventually delivered to Anderson the format for a show to be titled: Four Feather Falls, and the first draft script. Delighted with Gray's submission, Anderson sold the series to Granada Television in 1958 and naturally, Gray supplied the music, including five Western songs which were used throughout the series, sung by then-popular vocalist Michael Holiday, who was tragically destined to be killed shortly following completion of the series in an horrific car crash.

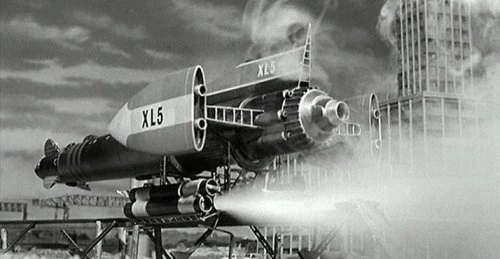

Both their personal and professional friendship solidly cemented, Gray continued to work with the Anderson's on television films, including Crossroads to Crime (1959), after which came the series which finally allowed both Gray and Anderson to find their own niche in their respective fields. That show was Supercar. Rather than a Western, this time the chosen genre was science fiction, and it was an immediate success, which helped paved the way for the undisputed classics that were to follow. On his personal approach to TV/film scoring Gray had this to say: "I try, particularly, to tailor not only to the visual but to the dialog. If I'm going to keep the music going behind dialog, I write accordingly and go into a very suitable background, very unobtrusive, very un-busy background whilst the dialog is going. Even if the action is fast, and when you come out of the dialog you go into fast action and probably fast music, I'll usually just sustain a long hold, or very slow moving holds behind the dialog because to me there's nothing worse than busy music going on behind dialog. I prefer composing and orchestrating for large symphony orchestra rather than anything, although I've had to go down along the electronic road many times in my career. But, generally, I like to write the correct kind of music for that which enhances the action in a film."

Also at this time, Gray was becoming increasingly interested in electronic music. This was decades before synthesizers were to become widely available so much of the equipment Gray employed he had he either procured or manufactured for himself. This led to an expansion of the North London recording studio he had set up in 1950. In his questing search for unusual and experimental instruments Gray discovered a French instrument called the Ondes Martenot, which had originally been developed from the Theremin, which would produce sound oscillations, which were controlled with a keyboard. Realising its potential, Gray bought one of the instruments and actually went so far as to study with its inventor, Martenot, in Paris.

With the creation of Supercar in 1959, Gray found an ideal use for the Ondes Martenot in the music for the futuristic series. He was so impressed with the results, that he would employ the Martenot to great effect almost a decade later when Gray composed the score for the Anderson theatrical release, Doppelganger (AKA Journey to the Far Side of the Sun ), and employed it for other motion pictures such as Dr. Who and the Daleks , Fahrenheit 451 and Island of Terror, the scores of which were composed by other composers. Gray explained his use of Electronic music thus: "At the time that I was starting to write electronic music for the early Gerry Anderson series, producing electronic music was a far different kettle of fish than it is today. At that time, one had to rely on tape manipulation; and on using any type of instrument to get a basic sound from which to work."

In 1963 Stingray became the Anderson's first marionette series to be filmed in colour, due to its larger budget and more elaborate production facilities. These also allowed Gray a larger orchestra than he had been able to use on any of the previous series. 24-piece orchestras had recorded Supercar and Fireball XL5whereas Stingray was recorded at Pye Studios with an orchestra of 38 musicians. The continued success of the Anderson shows quickly paved the way for the series that was destined to boast arguably Gray's most memorable - certainly his most popular with the general public - score. That show was Thunderbirds.

On Thunderbirds, Gray once again employed a 38-piece orchestra. On most of these series the music, as was the case with most television scoring of the 60's in Britain and the United States, was partially original and partially re-used. For Thunderbirds, Gerry Anderson had suggested that a military flavour in the music would be good for it since the show was a dramatic series with militaristic overtones. Gray's music was ideal and in fact many military bands have since adopted the Thunderbirdstheme into their programmes. About two-thirds of the episodes use original music composed specifically for the occasion; with the remainder re-using music written initially for other episodes, a practice made frequent by budgetary considerations.

For Thunderbirds Are Go! (1966), the first feature-length movie derived from the series, Gerry Anderson said he wanted a big symphonic sound. They settled on a 70-piece orchestra. The Thunderbirds Are Go! score was recorded over six sessions, engineered by Gray's old friend Eric Tomlinson at Anvil Studios near Denham. Thunderbird 6(1967), the sequel, used a 56-piece orchestra and Gray found it especially enjoyable to write that score inasmuch as the film's international locales allowed him to write in different styles, including Russian, Indian and Swiss. As he explains in his own words: "It's a rather humorous little story that when Thunderbirds Are Go! was going to go into production, Gerry called me into his office and he said: "Barry, I'd like to get the real sound of a symphony orchestra for Thunderbirds Are Go!. How many musicians would we need?" So I said: "Well, if you want a real symphony orchestra sound you'll want about a hundred and twenty." So, when Gerry had picked himself up from the floor, he said: "Well, how many could you do it with?" I said: "I'll do it with seventy." So it was decided then and there that I would have a 70 piece orchestra. A lot of the music in that score was not connected with the TV series because it was for different situations, but I did use and orchestrate the Thunderbirds theme and called upon it in snippets throughout the film. I must say that it was a most enjoyable score to do and we had most enjoyable sessions. We got a very, very excellent recording, which was done by my old friend Keith Grant at Olympic Studios in Barnes, London. We also recorded the Thunderbirds Are Go! LP at the same studio although on this I used a 54-piece orchestra"

The stirring and instantly recognisable Thunderbirdstheme, composed for the series and carried over into both features, while Gray's most successful composition - having been recorded many times by both himself and others - was not actually Gray's own personal favourites from his body of Anderson work. His actual preferences lay with his themes from Secret Service and Doppelganger.

For the Anderson series Secret Service - a series about an agent working for a secret organization called BISHOP - Anderson suggested to Gray that something in the style of Bach would be appropriate accompaniment, suggesting the French vocal group The Swingle Singers might be utilized. Acting on this, Gray flew to France to make the arrangements, but ultimately realized the budget afforded to the series would not accommodate them. However, during the flight home, his theme for a three-part fugue in the style of Bach was born and very successfully handled in England by the Mike Sammes Singers. As Gray was to remark sometime later: "Music theme composing is something you either can or cannot do. Fortunately, I have a sort of mechanism that triggers off when someone asks me to write something and I see an episode or film and get some kind of triggering off of the type of music the film needs. Also, I work best under pressure. If it has to be finished by tomorrow morning it'll be ready by tomorrow morning. It is something built in."

1970 saw Gray move from London to the small tax haven island in the English Channel of Guernsey. His studio was also taken along and was situated inside a former German bunker some fifteen feet below ground. The electronic effects recorded here were overdubbed on top of the orchestral recordings made in England. Four years later, Gray would score Space: 1999for his old friend Gerry Anderson. His involvement in the series was confined to the first season only, having been ignominiously ousted along with certain members of the cast and crew when American producer Fred Feinberger was brought in over Anderson's objections by the network to give the second season a "new direction" since they were unhappy with the series' first year. British composer Derek Wadsworth was drafted in to replace Gray, providing the second season with an entirely new music score. This rather sad turn of events was to be Gray's final actively direct contribution to the genre of television/film music.

Following the end of his creative involvement with Space: 1999and his active work with film scoring in general, Gray devoted himself to hobbies such as drawing, calligraphy - his letters to friends and fans are masterworks of fine penmanship - and the writing and illustrating of books on his adopted home of Guernsey. Then, early in 1979, he was invited to arrange and guest-conduct roughly ten minutes of his own compositions for the annual Filmharmonic Concert of Film Music, the proceeds of which benefited the Cinema Benevolent Fund. Gray accepted readily, and soon found himself directing a 93-piece orchestra through a specially arranged suite of his music from Doppelgangerand Thunderbirds. This presentation was recorded and issued on record in England, Gray's portion of which is the only available recording of much of that music. The Filmharmonic benefit was a major success and Gray was surprised and delighted to discover a large group of Anderson fans waiting at the backstage door at the end of the performance, seeking autographs. Many of them had gone so far as to bring their collections of old Century 21 mini LP's of his TV themes to be signed by the man himself. Concert organizer Sidney Samuelson was so pleased that he immediately requested that Gray compose the introductory stage show for next year's Film Performance. It was also around this time, Gray was asked to compose the Fanfare for the Royal Film Performance of 1980, to be performed by the Coldstream Guards Trumpeteers.

Throughout 1981, Gray maintained a close working association with Robert Mandell of ITC New York, which involved his re-arranging and re-dubbing of his music for the Supermarionation Space Theatre shows, 90-minute recompilations of episodes of various Supermarionation series from Stingraythrough Space: 1999. Other activities included the composing of a theme for International Rescue, a real life rescue operation formed in England inspired by Thunderbirds and with Gerry Anderson as honorary President. Gray also attended the Space: 1999 Alliance Conventions in Atlanta, Georgia and Columbus, Ohio and was a main guest at the 1982 Fanderson convention held in London, during which he played many of his famous themes. He also accorded a portion of his time to his duties as the resident pianist at the Old Government House Hotel on Guernsey, performing as much for his own pleasure as anything else during official dinners.

Gray had agreed to return to active TV work via composing the music for a new Anderson created series, but sadly such was not to be. Gray's involvement in the project was brought to an untimely close by his sudden death on 26 April 26 1984.

Although Barry Gray the man is no longer amongst us, he bequeathed to generations of TV viewers a creative legacy whose technical brilliance and inspiring creative sweep has become an enduring and integral part of our popular culture. From the child-like innocence of Twizzleand Torchy to the epic excitement of Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet , the musical ability of Barry Gray has subtly enriched the history of both the entertainment media, and our own person recollections.

Published on May 9th, 2020. Written by Peter Henshuls for Television Heaven.