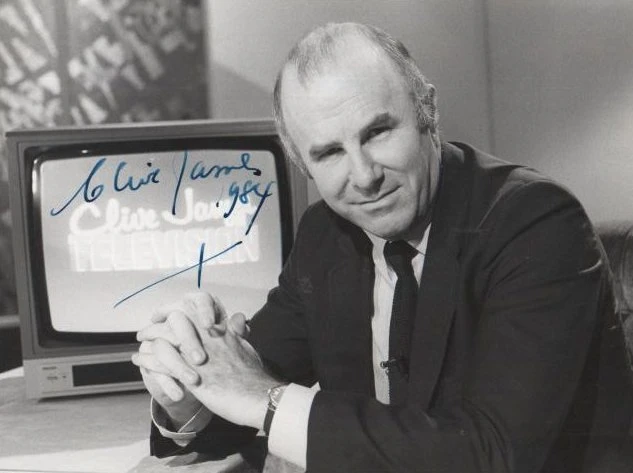

Clive James

‘I do like to hear people laugh and occasionally be the cause of that’

Clive James by Brian Slade

There are some personalities that are as memorable in themselves as the shows that they appeared in. One such gem was an adopted Australian who tried his hand at almost everything in the entertainment business, despite seemingly suited to almost none. That man sent us postcards from major cities, brought us bizarre television shows from overseas long before the internet, and of course introduced us to the talents of Margarita Pracatan. He was the inimitable Clive James.

James was born in Kogarah in New South Wales in 1939. He was actually named Vivian James, after Vivian McGarth, a popular Australian Davis Cup tennis player. After Vivien Leigh’s success in Gone With the Wind, James admitted he got tired of being sent to sewing classes by mistake, the name having become more accepted as a female one. Of the options presented to him by his mother for a change of name, he went with that of Clive, taken from a Tyrone Power movie character.

James never knew his father, who was cruelly killed in a typhoon when returning to Australia from a Japanese prisoner of war camp when young Clive was just five years old. He was raised by his mother, but he would admit that rather than be scarred by the emotional trauma of never knowing his father, he was actually blessed with an absurdly carefree upbringing. While acknowledging what a challenge his youth was for his mother, James would later acknowledge that like so many in the comedy business, ‘…one of the reasons why I grew up feeling the need to cause laughter was perpetual fear of being its unwitting object.’

Psychology provided the subject of Clive’s degree from Sydney University, but during his study he was forever writing…poetry, prose, criticisms were all flowing. He spent a year with the Sydney Morning Herald before heading overseas to the UK where he would enrol at Cambridge studying English while living a threadbare existence on the pretext that he would take menial jobs that allowed him to continue writing by night. He admitted in his memoirs that his knowledge did not come naturally and was based on a trial and error approach to life, recalling that, ‘In Sydney I had come of age but still had a lot to learn. In Europe, I forgot what little I knew.’

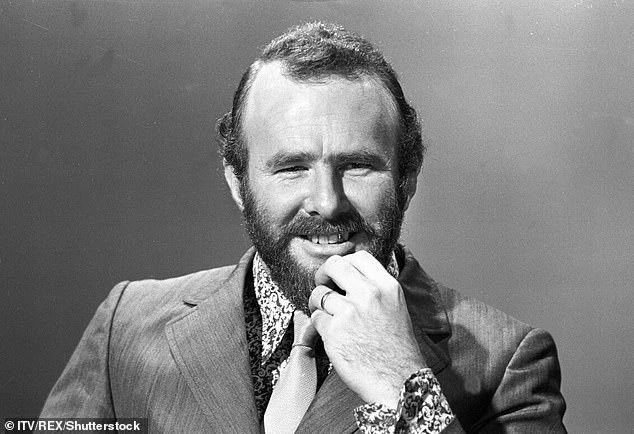

Clive James absorbed all that Cambridge and London in the sixties had to offer. ‘Byron kept a low profile in Cambridge,’ he wrote, ‘confining himself to booze, broads and leading a live bear around on a string. I was less inclined to hide my light under a bushel.’ He appeared on University Challenge and served as president of the Cambridge Footlights.

James eventually landed a job as a television columnist for the Observer in 1972. As a reviewer he spent the next ten years critiquing everything from The South Bank Show on Harold Pinter to episodes of Dallas and Charlie’s Angels. He delivered each review with the same level of wryly acerbic observation, such as his verdict on Perry Como’s Olde Englishe Christmas that, ‘Perry gave his usual impersonation of a man who has simultaneously been told to say “cheese” and shot in the back with a pointed arrow.’

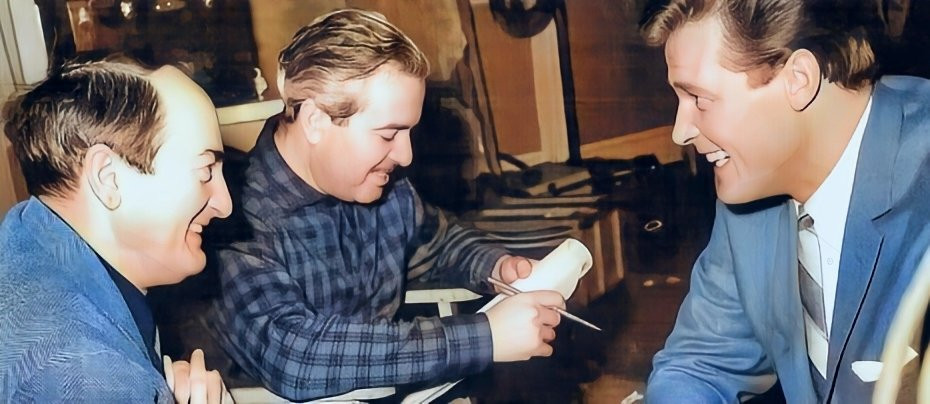

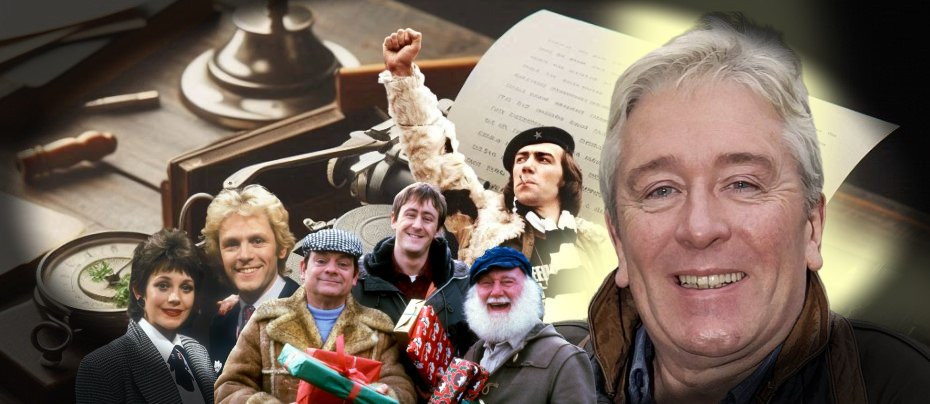

It was inevitable that such criticisms would eventually land James inside the beast that he espoused his opinions of. His first venture combined the glitz and glamour of Las Vegas with the world of Formula 1 for Clive James Live in Las Vegas. It was a precursor to his memorable Clive James’ Postcard from… series that would span six years in the 1980s and 1990s. As much about the curious inhabitants of a variety of the world’s major cities as the cities themselves, James combined his razor sharp observations with an innate relatability. Despite his never-ending thirst for knowledge and critical eye, nothing James ever presented on television spoke down to its audience or belittled the people that he met. Despite his vast intellect, he considered himself to be fair game for criticism.

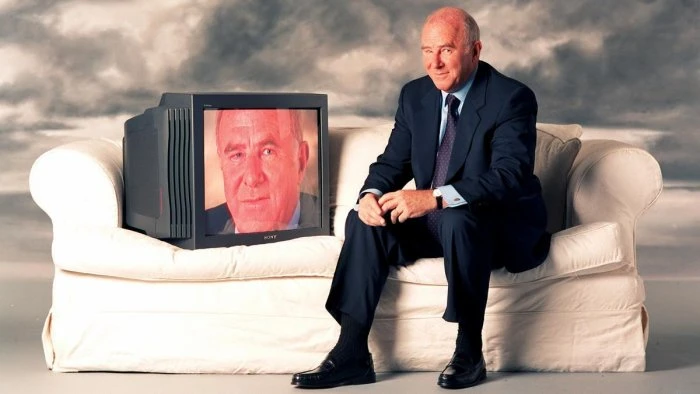

Perhaps more so than the Postcard… series, James’s on screen presence reached a greater audience with his Clive James on Television series. It showcased James at his best. Part chat show, part criticism, it put Clive’s rapier wit to task with some of the most bizarre television shows scattered around the world. This was of course pre-internet, so the arrival on British screens of clips from the excruciating Japanese game show Endurance, where contestants would suffer agonising pain in the name of entertainment, was ripe for the James treatment. James would host the show until 1988 before handing over the reins to Keith Floyd and subsequently Chris Tarrant, but it’s safe to say that the appeal was somewhat lost when the Australian said farewell.

James would morph his programme into different variations throughout the 1990s. Saturday Night Clive would become Sunday Night Clive and simply The Clive James Show, but it was always a successful move. James was capable of bringing in the extremes of the showbiz world for the chat show element of his programme, snaring the likes of Zsa Zsa Gabor, Tom Hanks and Tony Curtis, but it wasn’t a fluffy ‘here’s my new book’ kind of show. The critique of the weird and wonderful remained, never summed up better than by the introduction of one Margarita Pracatan, a Cuban-American cabaret singer whose appearance generated a cult following, so much so that she became the closing routine for the show. Stood behind her electric keyboard, covered in glittering costumes and feather boa, she would drop letters, and sometimes words, as her Hispanic accent would cover well known hits. James would say she was, ‘taking some of the world’s most recognisable songs and making them seem unfamiliar, new and strange.’ Pracatan’s spirit was infectious – ‘she is us, without the fear of failure,’ said James.

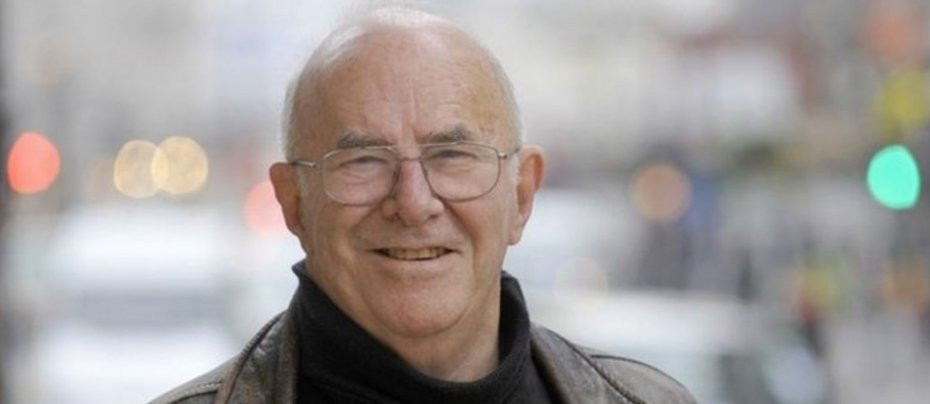

After the turn of the millennium, Clive James largely disappeared from screens. As much as he had a mastery of the medium, poems and writing were the hunger that drove him and that’s where he returned, eventually publishing over 40 books, including five memoir volumes. His recollections read very much as his television travel documentaries – absurdly intelligent, but lovably bursting his own balloons of pomposity before anybody else gets the chance. It’s why he remained in demand as a writer for newspaper columns up until his death in 2019.

Australia had a slightly different relationship with James. The population there knew him as a writer more than a television star and so the celebrity status that irked him in the UK, with all the accompanying autograph-hunting and wise-cracking comments in the street, didn’t follow him home. He rather enjoyed that escapism when he returned home, but whether writing about what he watched or hosting his own programme, British fans held him in the highest esteem for his influence on television.

Clive James was given a death sentence many times in later life, starting in 2010, but he continued to work as he defied the odds for nine years to survive. For those later years he wrote incessantly, displaying a wisdom and maturity he says he wished he had gained at a younger age. But his self-effacing humour and belief that his career and life had been blessed with great luck never left him. He said in a 2016 interview, ‘I do like to hear people laugh and occasionally be the cause of that…that was the best part of my career.’ British viewers of the right age will be forever grateful for being the ones to grant him that pleasure.

Published on April 8th, 2022. Written by Brian Slade for Television Heaven.