Windsor Davies

Biography by Brian Slade

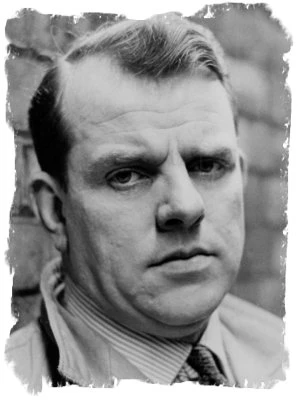

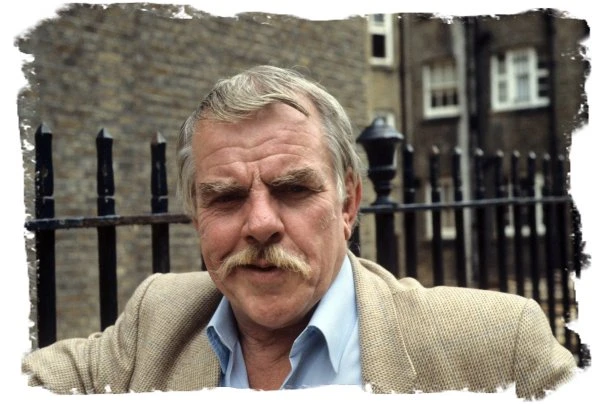

It’s rare that one small catchphrase can transform a career in television, but in 1974 that’s exactly what happened to the lead actor of hit comedy It Ain’t Half Hot Mum. The simple command of ‘Shut up!’ was so recognisable that it made Windsor Davies one of the most well-known faces, and voices, on British television.

Despite becoming so easily identifiable with his booming Welsh accent, Windsor Davies was actually born in Canning Town, in London, in 1930. His parents were Welsh and in the Second World War, 10-year-old Windsor was despatched to relatives in the Ogmore Valley in South Wales. It was here that he trained for the career he expected to pursue, attending teacher training college in Bangor after taking turns working in factories and down the mines. His teaching aspirations were placed on hold as he did several years of national service in North Africa. Here he would encounter the kind of officers that he would mimic years later in his television career.

At a comparatively late stage – by now he was in his thirties – in 1961, Davies took a short drama course at Richmond College. Had his wife not encouraged him to do so, by his own admission he would likely have remained a teacher. By now he had settled in South London with another teaching job, but the acting bug was biting. After touring with Cheltenham rep, Davies would gather an eclectic mixture of entries on his acting CV during the 1960s, starting with ITV drama Probation Officer. It was an inauspicious debut, Davies later admitting that, ‘I didn’t know one end of a TV camera from the other and I didn’t know how to tackle the job properly.’

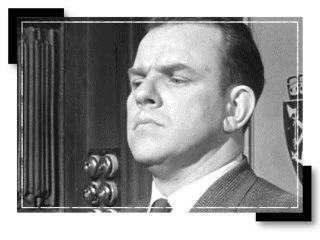

Other early roles included some of the most familiar shows on screen during the decade, including Dr Who, Z-Cars and Dixon of Dock Green. The majority of his roles benefitted from his authoritative aura, although he displayed the full range of his skills in 1966 BBC play Talking to a Stranger, in which he gave a far more discreet performance as Detective Sergeant Wilson investigating a suicide. The play was a highly acclaimed quartet of programmes starring Judi Dench, showing the same crime from different points of view. It was a very well received piece and Davies’s performance in part three – Gladly, My Cross-Eyed Bear – showed a gentler side to his performances.

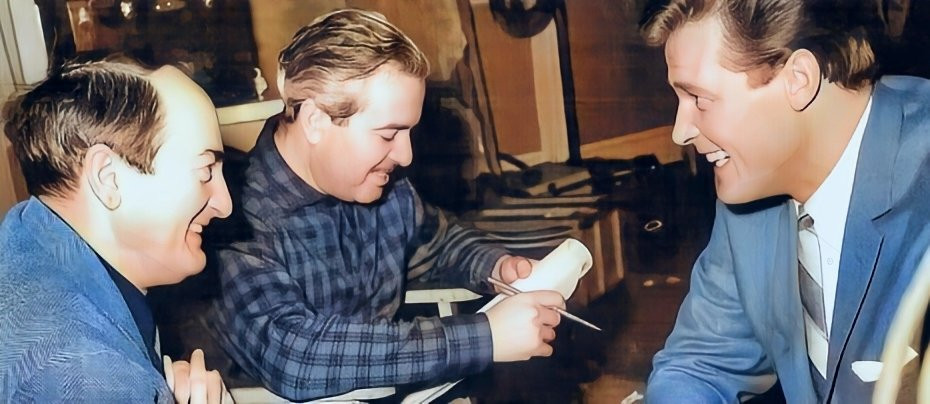

When David Croft and Jimmy Perry began casting for their new military comedy based in India, It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, they were looking for a Sergeant Major type to counteract the inept collection of performers in a Royal Artillery concert party. Their first thought had been Leonard Rossiter, but having sent him the script for their pilot show and arranged a meeting, they both felt that Rossiter carried a patronising attitude to the programme and decided to look elsewhere. When they asked Davies to read the part in his Welsh accent, Davies having originally tried a cockney approach, they were immediately convinced of his suitability and by the time he had returned home, Davies was asked to call his agent as he had been offered the part.

Croft was delighted with his leading actor. ‘The part fitted him perfectly,’ he commented. ‘He relished it and made it his own. He was completely unselfish in his relationships with the other actors and was a perfect member of the team from that day forward.’

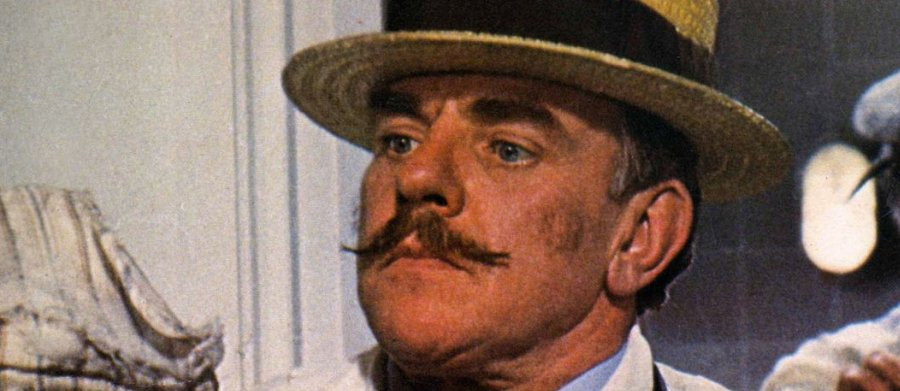

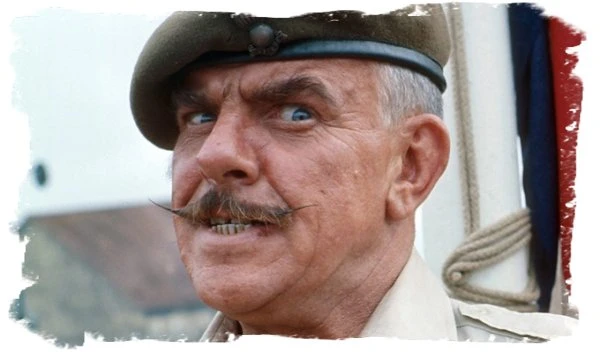

The premise of It Ain’t Half Hot Mum was that Sergeant Major Williams was in charge of a concert party as the Second World War reached its conclusion. Williams was in a world of his own. His superiors were tea-drinking aristocratic types, more interested in cricket scores and social standing than military manoeuvres. The troupe themselves were a ragtag collection of singers and entertainers that Williams frowned upon. As far as he was concerned, the best thing for them would be an excursion up the jungle and a confrontation with the Japanese.

Davies’s performance as the Sergeant Major is legendary. Bulbous red in the face, chest out, full-on military anger at all times, his bellowing instructions were the highlight of the programme, without which none of the characters were really strong enough to sustain the show. His delivery of some lines ensured that a whole raft of catchphrases would follow him for the rest of his career. ‘Shut up!’ was bellowed every time he got an answer to a question from one of his subordinates that he didn’t actually want an answer to in the first place, as well as ending the final credits. ‘Oh dear, how sad, never mind,’ was another sarcastically delivered put down, and his relentless mimicry of upper-class piano-playing ‘La-de-dah’ Gunner Graham was merciless.

Most significantly, however, Davies inadvertently stumbled into a double-act with Don Estelle, who played the diminutive singer ‘Lofty’ Gunner Sugden. The physical differences between the two opened up an avenue of comedy that the nation warmed to, to the extent that the pair scored a number one hit with a re-working of Ink Spots single Whispering Grass, and they would be seen at publicity events and adverts as a duo.

For all the talent that Davies put on show in It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, the critics were ready to bring the show down. As popular as it was, Michael Bates being ‘blacked up’ to play Bearer Rangi Ram did not sit well even in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Sergeant Major’s frequent dismissal of his charges as just ‘a bunch of poofs’ may have been reflective of how such characters did indeed talk at the time the show was set, but it didn’t make it any more welcome for the show’s audience. The bulk of the programme is Croft and Perry at its finest, but it was always going to be difficult to convince a changing audience that its material was appropriate.

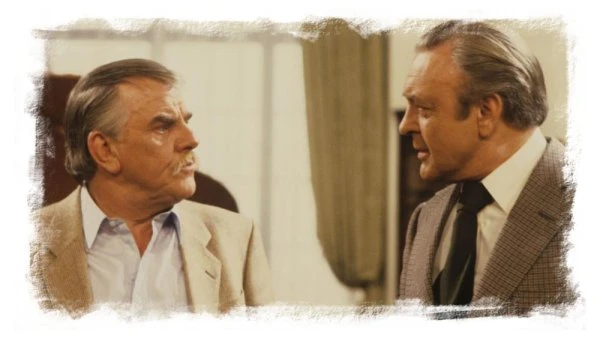

When It Ain’t Half Hot Mum ended, Davies was uncertain as to whether there would be another starring role around the corner. He firmly believed that an actor should always be thinking about his next role as one could be out of work for no reason in an instant. He needn’t have worried. Hot on the heels of his jungle excursions came the more sedate surroundings of Never the Twain, where for eleven series Davies would star with Donald Sinden as rival antiques dealers in neighbouring stores. Sinden’s Simon Peel gives the impression of a well-to-do dealer used to the finer things in life, frowning on Davies’s Oliver Smallbridge as more of a common nic-nac shop. Smallbridge was a more subdue role for Davies, and necessarily so, but his interplay with Sinden made it one of Thames most successful comedies of the 1980s.

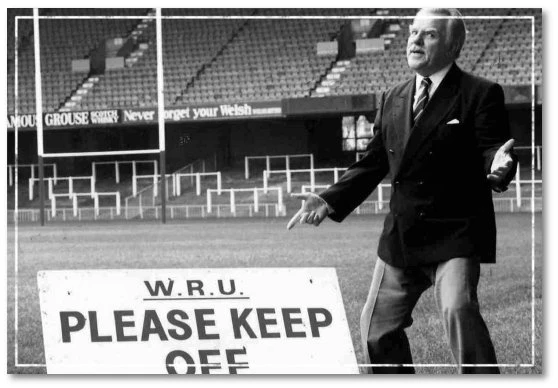

When Never the Twain ended in 1991, it signalled the end of any real starring vehicle for Davies. Despite this, he remained one of the most recognisable voices in the business. Between his sitcom successes, he had provided his talents to a number of projects, including The New Statesman and Gerry Anderson’s television show Terrahawks. And in 1978, Davies, appeared in what he would later describe as his favourite role, that of Mog Jones in a one-off comedy called Grand Slam. As Welsh rugby fans let loose in Paris, Jones is the leader of the group and ends up behind bars yelling ‘Wales! Wales’ from within his cell. Filmed on location during a five-nations weekend, as an ex-rugby playing Welshman, Davies was in his element.

Davies retired in later life to the south of France, where he lived with his wife of more than 60 years and without whose advice he might never have even tried acting. He passed away in 2019 at the age of 88.

That the most iconic role in the career of Windsor Davies is effectively confined to the political correctness dustbin is a shame, given that it made his career. However, perhaps the abrasive nature of Sergeant Major Williams is best left for private screenings. Never the Twain, while not being a particularly ground-breaking series, does present a gentler Windsor Davies across its eleven series. While the nation’s viewers of a certain age will always associate Windsor with the bellowing ‘Shut Up,’ maybe it’s more befitting that a more discreet role be the one most often repeated representing the gentle and generous man that Windsor Davies actually was.

Published on April 13th, 2020. Written by Brian Slade for Television Heaven.