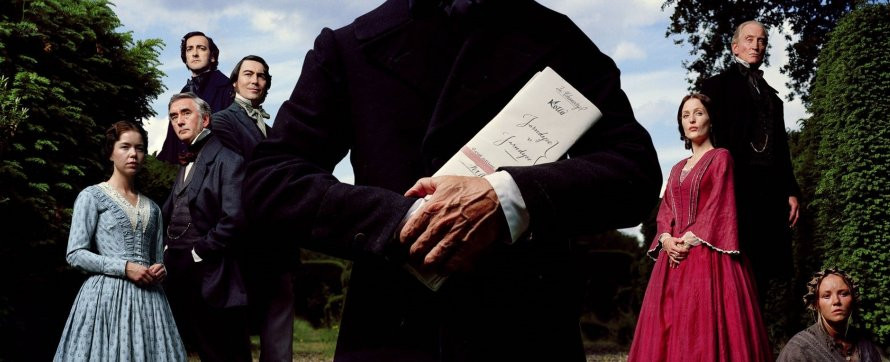

Mistral's Daughter

1984 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

If one can see clearly through the soft focus and the soap in one's eyes, Mistral's Daughter is a great example of the American miniseries in the format's glory days. Made deliberately as "event television" with the hardheaded, unromantic business objective of domination of the US ratings for a whole week, the hyper-romantic drama is visibly the product of considerable commitment and cash investment. The $15,000,000 budget was a huge sum for the time, but it can still be seen where it all went - in the prestigious casting, the outstanding production values, and, above all, the extensive location work in France when overseas production was still a rarity.

It is based on the bestseller by Judith Krantz, whose "sex and shopping" novels were perfect miniseries fodder for the consumerist early Eighties. This seems to have been an unusually ambitious project for her, involving at least some historical research, as well as building on her own experience working in France. It nevertheless retains a strong whiff of S&S as the story of struggling artists and models rapidly turns into one of easy success in true Eighties style. Krantz happened to be married to a Hollywood producer, whose company made the miniseries.

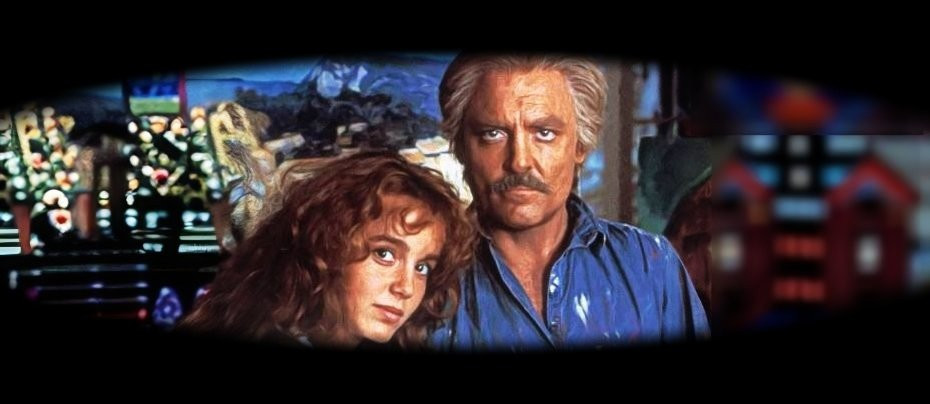

The Mistral of the title is a fictional painter in the Paris of the Twenties that was in retrospect given a heavy varnish of glamour mainly by American "expats" such as Hemingway (the reality is that France was still recovering from the total devastation of the Great War). Mistral, who takes his name from a dangerous tempest, is based unsubtly on Picasso and Matisse, despite both being mentioned as separate people in the script, with hints of Cezanne, Gauguin, and Chagall, Mistral's final series of paintings clearly referencing the extraordinary collection in the Chagall Museum in Nice. Some of the paintings attributed to "Mistral," the best of which look like very good Impressionist pastiches, were in fact commissioned from John Bratby, a British artist whose real life resembled Mistral's in that he once enjoyed a high reputation as a rising talent - which, like most such fashions, did not last - and in that he also treated his wife appallingly.

As seems to be expected of a successful Parisian artist, Mistral is vain, arrogant, self-centred, secretly needy, and absolutely disgusting in his attitude to women. One of these is Maggy (sic) Lunel, an innocent young Jewish girl from the Loire who arrives in the City of Light with dreams of becoming an artist's model.

To be honest, the plot, with the exception of a powerful Wartime sequence and a moving pay off in the final episode, and most of the characterisations are contrived to the point of cartoonish. It is a bit shocking to see the names of two very distinguished and talented British writers, Terence Feely (Callan, Arthur of the Britons, Number 10) and Rosemary Anne Sisson (Elizabeth R, The Duchess of Duke Street), in the credits: one can only assume that they did the best with what they were given by the novel, turning in a tight, efficient script, grateful for the opportunity to get some big American money for a change.

Anyway, the viewer is not here for the story as much as the atmosphere, and in this respect Mistral's Daughter really delivers. It is, at least in terms of style, the perfect romance, a feast for the senses, elevated by the positively artistic photography of the landscapes of Provence and the soaring high chords of Vladimir Cosma's sumptuous score. The highlight of the latter is without question the most famous aspect of the production, the ballad "Only Love," sung by Nana Mouskouri in the distinctively French chanson style. It was an international hit in its own right at the time, reaching Number Two in the British singles chart and Number One elsewhere.

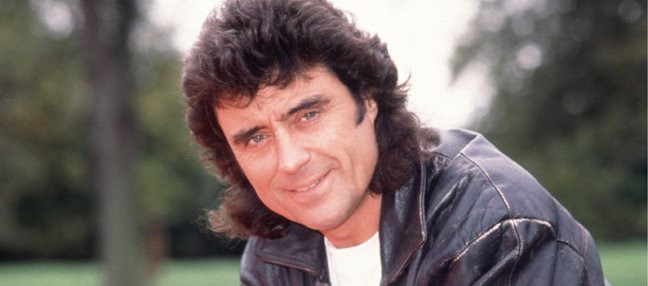

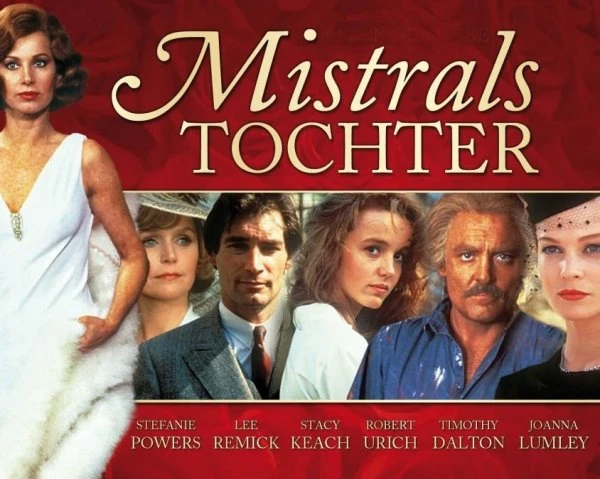

The shallow characters themselves are given more depth than they probably deserve by a very strong cast. His, er, legal problems in the UK that began not long before Mistral's Daughter was broadcast may have deprived Stacy Keach of the acclaim his performance as Mistral would surely have attracted otherwise and cast a long shadow over his career. He is a consistently fascinating actor, combining a powerful virility that dominates any scene in which he appears with the ability to convey a subtle detail that changes everything. He puts this combination to particularly good effect as Mistral when the aggressively assertive artist sometimes lets slip a tiny hint of self doubt. At these moments the viewer wonders how much of Mistral himself is just an act, and whether he is secretly living in fear that he will be revealed as a fraud.

The main theme of the story is obviously intended to be the now standard trope of the brilliant artist so committed to his work that he considers the people around him of little importance. Yet it is never explained what Mistral is trying to achieve in his work or why it is important to him. Moreover, most of the other characters seem to be as selfish and amoral as Mistral himself, even if they hide it better and are outwardly more agreeable.

Indeed, two of the characters we are apparently supposed to view as villains, his ultra-supportive wife (the always magnificent Lee Remick) and the neglected daughter who is nevertheless the one who turns up to nurse him when he falls ill (Caroline Langrishe pre-Lovejoy), both of whom are understandably embittered by his open contempt for them, are arguably among the people most entitled to our sympathy.

That much of our sympathy actually goes to a character who comes across at first as no more than a coldly efficient businessman is due to a typically intelligent performance by Ian Richardson (Private Schulz, Porterhouse Blue, House of Cards). He is humanised by his suffering when, as a Jew in German occupied France, he is forced to go on the run. A brief change of expression when joy turns to despair as he sees that his old friend Mistral has seen him, and then realises Mistral is not going to help him, is in itself a micro-masterclass in acting. This episode also exposes a truth rarely acknowledged, that life in France during the War was necessarily a matter of compromise, and, much as some later exaggerated their connections with the Resistance, the Wartime conduct of most French "intellectuals" is not an edifying tale.

Stefanie Powers, just off Hart to Hart, is very attractive as Maggy but it really was asking too much of a woman in her early forties to play the character in her teens. A pre-Bond Timothy Dalton and perennial miniseries favourite Robert Urich, who had starred in an adaptation of another Krantz novel the year before, are well cast as the handsome, well-mannered rich men who successively fall for Maggy, but cannot disguise the fact that their characters are no more than plot devices and could easily have been interchangeable.

Joanna Lumley (The New Avengers, Absolutely Fabulous) puts on an occasional American accent as Maggy's convenient New York friend while the elegant Stephane Audran is Maggy's equally convenient Parisian friend. Other familiar faces include Angela Thorne as a loyal English nanny, Wolf Kahler as an art loving German occupier, Michael Gough as an Irish American Cardinal, and Victor Spinetti as an Italian American dress shop owner. A young Kristin Scott Thomas makes a mark in a small supporting role as an object of Mistral's passing sexual interest. Charlotte Allen is an absolute delight playing Maggy's granddaughter as a child.

Sadly the character, the Mistral's daughter of the title, is far less interesting when she grows up, as is her mother, Maggy's daughter, around whom the whole plot revolves. We are never really given much reason to care for either. There seems to be no real heart at the heart of the project, and, for a supposed love story, very little understanding of love. The whole thing is not so much "Only Love" as only style, with no substance - but that style is still memorable.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 30th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.