Star Trek: Picard - Season 3

“There are two main reasons for the popularity of Season Three. Most obvious is the fact that it gave the fans what they wanted all along”

Star Trek: Picard - Season Three review by John Winterson Richards

It seems that, as with so many things these days, the way to build a following as a film or television critic is to take extreme positions, either totally for or totally against something. You will find there are many people who will agree with you and will love you for endorsing whatever their own opinion might be. Yet for those of us who prefer at least to try to be strictly honest, life is rarely, if ever, that simple. On the one hand, there has never been a perfect work of art of any sort: part of the whole point of art is that it is an eternal quest for perfection, eternal because it is hopeless. At the same time, and at the other end of the spectrum, it is almost impossible for a group of professionals to work for any length of time on any project, no matter how bad, without it having at least some redeeming features.

So it is difficult to imagine a show that really deserves a rating of 100% (even if I, Claudius, which happens to feature the future star of Star Trek: Picard, may be as near as we can get) or of 0% (even if it is possible to think of a number of projects that come close).

Applying all this to Star Trek: Picard, a lot of people who really know their Star Trek, and whose opinions deserve to be taken seriously, took a very extreme position against the first two seasons only to be converted to taking an equally extreme position in favour of the third. As is often the case, there is none so zealous as a convert. It is respectfully suggested that neither extreme position, for or against, is completely justified. On balance, this reviewer rather enjoyed Seasons One and Two but felt that they had some major flaws - and exactly the same words could be applied to Season Three.

However, there is a difference of degree and that difference is everything. Star Trek: Picard deserves credit as a show that improved with each season: contrary to what audience appreciation ratings might suggest, the second was much better than the first; and practically everyone agrees that the third was the best of the three by a mile.

There are two main reasons for the popularity of Season Three. Most obvious is the fact that it gave the fans what they wanted all along, a reunion of the Star Trek: The Next Generation crew and what is almost certainly a dignified final farewell to that show. Where the original Star Trek had ended on a high note with Star Trek VI: the Undiscovered Country, there was general feeling that the feature film Star Trek: Nemesis was an unworthy conclusion to The Next Generation. There had been high hopes that Star Trek: Picard would provide the grand send-off that Nemesis should have been, but in its first season it went off in a completely different direction with most of the emphasis on entirely new characters. This disappointment explains much of the excessive unpopularity of its first two seasons. Equally, the fact that the fans were pleased at finally getting their way may have contributed to their extremely positive reaction to Season Three. Fans are more inclined to like something if they feel their feelings have been taken into account. This has been demonstrated several times recently in relation to other major franchises, including the DC Justice League, Spiderman, and Sonic the Hedgehog.

The second reason for the success of Season Three is harder to pin down. The first two seasons were a deliberate attempt at a more "modern" style and tone. It did not go down well with long established fans, for whom part of the continuing appeal of The Next Generation is nostalgia. It is the product of a simpler, more optimistic time. Updating it to suggest that the future would reflect the uncertainty, social decay, and paranoia of the 21st Century struck a sour note and missed the whole point of Star Trek: we want - we need - to believe that the future will be better.

Season Three was put in the capable hands of Terry Matalas, a man whose involvement with Star Trek goes back a long way - he began his career on Voyager and Enterprise - and who seems to understand the underlying reason for its appeal. He therefore stripped it back to basics and gives us a show that somehow "feels" more The Next Generation, while still using the latest effects and visual technology. It helped having the old cast on hand, but he and his team also made clever use of the script, production design, and music to put together episodes oddly reminiscent of their 1990s equivalents, except with much better production values (being honest, the old show was produced on the cheap in many respects and, as usual, the very elements that looked modern back then now look the most dated).

The story and dialogue are full of references, both explicit and subtle, to what has gone before. Events in the past are shown as having ongoing consequences. There are more "Easter eggs" than on a supermarket shelf in March. There are welcome cameos from a favourite Voyager character and a memorable Next Generation antagonist. A brief appearance by a tribble is guaranteed to make a fan smile. It was a particularly nice touch to give a respectful nod to Constable Odo (the late Rene Auberjonois) from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, neatly built into the central story without him being named. Star Trek fans are the sort of people who notice and appreciate such things.

Yet the main selling point of the show is still that it got the band back together. While most episodic television shows maintain professional courtesy on their sets - the production schedules these days are punishing and there can be no tolerance for the sort of egotism seen on film sets - they are rarely places where deep friendships are forged, not least because the last people one wants to see after a very long day at work are the people one was just with. The Next Generation was a famous exception. The cast really bonded, and their easy interaction at conventions and the like suggests that these people are genuine friends - that or even better actors than we thought.

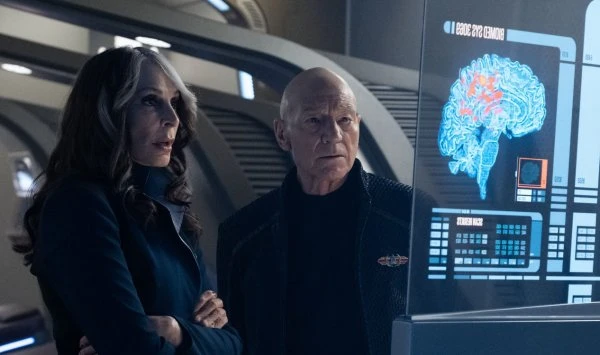

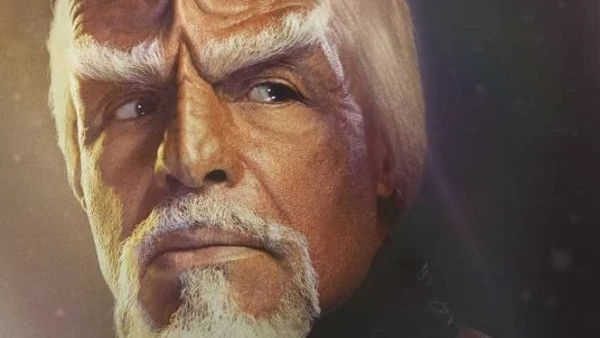

This comes through on screen. The scenes with Admiral Picard (Sir Patrick Stewart) and his old "Number One" Will Riker (Jonathan Frakes) are a joy, one of the best portraits of a straightforward male friendship on television in any genre. Almost as good is the slightly more competitive friendship between Riker and Worf (Michael Dorn). Worf also gets a great entrance and, as usual, most of the best lines.

The dialogue they are given is worthy of them. There are however some false notes. A brief conflict between Picard and Riker seems forced, as is Riker's subsequent temporary descent into despair. This sequence seems totally out of character for both men. Picard also has some artificial conflict with Dr Crusher (Gates McFadden) and later Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton) for reasons that do not stand much scrutiny. While the reunion would not be complete without Brent Spiner, and he enjoys himself in multiple clever variations on a theme, even the script seems to acknowledge that it is getting ridiculous how he keeps coming back from the dead, especially after Data's emotional "farewell" in Season One.

Meanwhile, Riker has another contrived conflict, this one with his wife, Deanna (Marina Sirtis). The scriptwriters have obviously been taught that conflict is good for drama. By contrast, Gene Roddenberry wanted interpersonal conflict banished from his idealised Federation because he wanted to believe humanity would move beyond it - despite being rather prone to it himself in real life. While Roddenberry's ideal was always too unrealistic to be credible, conflict for the sake of conflict is just as unconvincing. Surely there is enough room on the middle ground for compromise between his position and the Picard writing team's. Conflict should flow naturally from character and events. It does not always do so here.

There are many other points that strain both credibility and consistency with the rest of the franchise. Part of the appeal of Star Trek is that it was about a hierarchy and about how the characters were progressing up it. This was as important to the characters themselves as their actual adventures, and the risk to their careers was as much a factor in their decision making as the risk to their lives. Yet Picard has several people with questionable backgrounds, to put it mildly, jumping up the ladder very quickly. Other characters give the impression that Starfleet's selection and screening processes in general leave a lot to be desired. Then there is Picard and Riker's casual assumption that they can just commandeer a starship. Remember the difficulty Admiral Kirk and his crew had doing this in Star Trek III: the Search for Spock? Evidently Starfleet do not because they would surely have tightened procedures if they did.

It is no surprise that Picard and Riker turn out to be right. They eventually get their way in spite of the open hostility of the Captain of the ship in question. At this point the chain of command goes completely bonkers: it seems an Admiral on the Retired List outranks the appointed Captain of a vessel on his own command deck but an Acting Captain outranks the Admiral.

Starfleet in general comes across as pretty amateurish. There are a lot of obviously wrong decisions, some of them made by our heroes. A supposedly unsympathetic character who opposes endangering five hundred lives to save four is clearly in the right. Events appear to justify him. The same mistake is made again much later when we are invited to rejoice as four lives are saved apparently at the cost of unnamed thousands offscreen.

There are many other storytelling choices that might be questioned if we were not enjoying ourselves so much with our old friends. Some regrettable reversions to the negativity of the first season rather undermine the return to the ethos of The Next Generation. Indeed the season begins with a respected character incinerating a disabled opponent on the ground. There might be a defensible tactical reason on that occasion, but the process is repeated later as if a matter of routine. When did Starfleet abandon "set phasers to stun"? At one point Picard himself seems resolved to execute a prisoner summarily. It remains unsettling that the abuse of illegal narcotics is still widespread in the 25th Century Federation. There is even a criminal underworld, complete with a Vulcan ganglord - even if one cannot argue with his rationale that, since crime is inevitable, it is logical that it should be organised.

It would also be disappointing if the recent fashion for using swear words to emphasise emotion has not died out in a supposedly more advanced culture. They sound particularly out of place coming from the famously self-controlled Picard.

Yet it should be stressed that these lapses do not alter the fact that the basic architecture of the script is solid. It begins with two threads, the main story concentrating on Picard and Riker responding to a request for help from an old friend, and an apparently independent subplot involving Raffi (Michelle Hurd) from the first two seasons wandering around said criminal underworld. These two plots converge, and, one by one, the other veteran characters from The Next Generation all become involved. The way this happens seems perfectly natural and uncontrived.

There is a very good guest appearance from one of the strongest supporting characters from The Next Generation whose character arc was never resolved properly back in the day - possibly due to bad career advice. This leads to some of the best acting moments in the franchise. Later a huge twist reveals a new enemy, or rather the return of an old enemy, complete with a familiar voice. To say more would be to risk spoilers, and that would be a pity because both these dramatic turns in the plot are well conceived and well executed.

Another familiar voice turns up in the final episode in a role that has delighted fans and a familiar face makes a somewhat incongruous appearance in a mid-credits scene. Yet another beloved voice, this one associated with someone no longer with us, is used organically in a tasteful tribute. The eagle eyed will recognise the Fleet Admiral: yes, she really was ambitious.

The real appeal is still the return of the Magnificent Seven, and they all fit comfortably back in their parts as if they had never been away. The humorous banter between them is unforced, and it is pleasing how they all contribute something to beating the insurmountable odds with which they are confronted. This was not always the case in the feature films which seemed to ignore some of them in the name of brevity.

Jeri Ryan returns as Seven of Nine and Orla Brady has a couple of scenes as Picard's Romulan housekeeper - it really is hard to be certain if she is his girlfriend or his carer. Apart from them and Hurd, the rest of the new characters introduced in Seasons One and Two have been dropped fairly heavily. One can see the commercial and narrative reasons for this, but the actors surely deserved at least a respectful mention of the parts they played. There was an opportunity to give at least one of them a proper ending to her character's arc, which instead remains curiously up in the air and gives the plot something of an avoidable consistency problem.

An almost unrecognisable Amanda Plummer goes gloriously over the top as the apparent principal antagonist. Ed Speleers does well in a poorly conceived but pivotal role, even if the part is not sufficiently strong to provide the male lead in the "follow up" show for which the conclusion seems to be begging. A show based on the initially antagonistic Captain Liam Shaw, played to perfection by Todd Stashwick, might have been a better proposition. He steals almost every scene in which he appears, something that takes doing in this company. At first he comes across as an obnoxious idiot, but hidden depths are revealed gradually. It turns out that he has understandable reasons for some of what he says and does, he sees things that others do not, and his judgement is usually good. In the end he reveals a certain nobility beneath his boorish exterior. This is first class character construction, providing the framework for first class acting.

The effects are good even if they are obviously effects. The destruction of a Starfleet recruitment base by a "portal weapon" which displaces large masses is very well done. A couple of epic space battles look duly spectacular despite being wholly unrealistic if one stopped to think about them - which, happily, we are not given time to do. There are some beautiful images associated with what is assumed to be a nebula.

A very strong design team, including the Star Trek legend that is Michael Okuda, stays true to many of the concepts of The Next Generation but updates them, and gives them a greater texture and depth that was never really possible on the budgets they had in the Nineties. This strengthens the impression that Picard is taking place in a universe in which people might actually live rather than on a set. Many of the starship designs are aesthetically very pleasing.

The drama benefits a great deal from one of the best soundtracks of any recent television show. The composer Stephen Barton, assisted by Frederik Wiedmann, had no qualms about raiding the rich musical back catalogue of the whole franchise and then adding their own little twists. The whole is a graceful tribute to the work of Alexander Courage, Jerry Goldsmith, and James Horner. The use of a subtle variation of the Klingon attack theme to introduce Worf was particularly clever, and the stately, elegiac theme from Star Trek: First Contact was the perfect choice for the end titles.

The season was evidently structured deliberately and very carefully as a whole. It starts relatively slowly, but then the pace picks up. The fourth episode is a good old fashioned "starship in a hopeless situation with time running out" classic helmed by Frakes, who is also one of the franchise's most accomplished directors - among other things, he also directed First Contact, generally held to be the best of the later Star Trek films after The Undiscovered Country. Following that there is a pause to regroup before more revelations and then a truly cinematic action-packed finale.

Yet, for all the sound and fury, this is a thoughtful, reflective show that deals with mature themes. Maturity is itself one of them. It is good to see a television show in which older people are valued and shown as having something to offer. Since most hard core Star Trek fans are now likely to be well over thirty - one suspects recent entries in the franchise have failed to find much love in the younger generation - this has probably endeared the season to the franchise's main fanbase even more. Indeed it is quite subversive that an important plot point comes when young people under 25 turn out to be unreliable because their brains are still growing and are therefore more susceptible to manipulation.

Cue knowing grunts of approval from ageing Trekkers all over the world. Incidentally, like much of the science in Star Trek, the neurobiology behind this is accurate.

Even more subversive is an explicit warning against the dangers of collectivism and centralisation, both in technology and decision making. Trek has never been so libertarian. There is also a moment of vindication for those of us who have always been suspicious of the transporter system (it basically disintegrates you every time and then copies you exactly somewhere else, in effect killing you and cloning you, begging the question, which the show never answers, if the person who comes out of the transporter is the same person who went in).

The main theme is, of course, family - and friendship, and the overlap between the two, which was always the subtext of The Next Generation. To be honest, the Picard Season Three script often rather beats us over the head about this when it could have made the same point with far less "on the nose" dialogue. It is nevertheless a very good point and at least some of the many scenes in which it is made have real emotional weight.

Finally, as the President of the Federation reminds us, quoting an old comrade of his father's, there is always hope, there are always possibilities.

This point is made very powerfully in that excellent fourth episode when, after Riker's crisis of faith, our heroes manage to get out of an apparently hopeless situation. It is reinforced in the final battle when the situation seems even more hopeless. The show is a powerful reminder that just because we see no grounds for hope does not mean that there are none and that trying our best in the absence of any prospect of success can sometimes open up opportunities that we did not know existed or that did not exist before we tried.

This is a lesson the world really needs today.

It might be said to have applied to the show itself. Like most of the other big intellectual properties, including Lord of the Rings and Star Wars, the Star Trek franchise has been treated as a cash cow in recent years following a well-established management consultancy system, the BCG Matrix. The brand name has been stamped on second rate "content" with a view to making as much money as quickly as possible before it loses all value. Season Three of Picard, possibly along with Season One of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, proves that things do not have to be this way. Fans are beginning to chat online about the potential of "Terry Trek." The suggested follow up show, already given the unofficial designation Star Trek: Legacy, has not been approved at the time of writing, but studios and producers are beginning to treat fanbases with more respect after some recent disasters and surprise successes. They would be fools to ignore the very positive fan reaction to Season Three and the money on the table it represents. There is always hope, there are always possibilities.

Perhaps the same may yet prove true of our culture as a whole. It will be counterproductive if the studios conclude that the lesson of Season Three is that the future lies with legacy characters. On the contrary, what they need to do is invest more in originality, to build the franchises of the future, rather than exploit the originality of previous generations until they are drained of all that made them special. The lesson of Season Three is instead a simple one, the oldest one in business: offer people what they like and they will buy it.

It would be overstating things to imply that Picard is a game changer. Nor is it, like The Next Generation itself, one of the all-time greats. Some generally intelligent people rather overreacted in condemning the first two seasons and then overreacted the other way in imputing to the third a perfection it does not possess. It is simply a well-made show produced by experienced professionals who really knew their product and their market.

Yet when one has finished with all the hard-headed reviewer stuff, there is still one more thing that has to be said. Forgive the subjectivity, but this old Trekker was surely not alone in enjoying a moment of intense happiness on seeing the seven veterans together on the bridge of a starship for one last adventure and hearing Picard giving the familiar order, "Engage."

Such happiness is not something one often feels watching television. It should be cherished whenever it happens to turn up.

Published on April 27th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.