Metal Mickey

1980 - United KingdomReview – Brian Slade

In the modern digital world, the idea that a successful television show on a commercial station would only be available to a percentage of the viewing public would seem absurd, but with the 1970s ITV franchises it was commonplace. So when in 1980, a tin can with burning red eyes, tense Christmas tinsel on his head urging his public to ‘Boogie, boogie, boogie,’ appeared in a programme called Metal Mickey, he may have been an unexpected site for ITV viewers in many regions of the country.

Mickey had made his first appearance in a regional Saturday morning programme called Saturday Banana. This was a show running up against Multi-Coloured Swapshop in the battle for young viewers as they prepared for their weekend. Made by Southern TV, it wasn’t picked up by all the regional incarnations of ITV. Hosted by Bill Oddie, it suffered from low budgets, the ongoing battle with Noel Edmonds’s runaway success on the BBC and comparisons to Tiswas, by now the pinnacle of ITV’s more rebellious Saturday morning offerings. Despite Oddie’s determination to give kids a less diluted form of entertainment than the reliable offering from Noel, it lasted only one series…but it did give birth to Metal Mickey.

Producer Humphrey Barclay had quite the Midas touch with comedy, but with production credits on such a range of successful shows as I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again, Two’s Company, Mind Your Language and at the other end of the diversity spectrum, Desmonds, Metal Mickey sticks out like a sore thumb. Barclay had seemingly seen the robot on now-disgraced Jim’ll Fix It and liked the robot enough to commission a show.

On reflection, despite the dubious premise of a college genius inventing this 5 foot boogie machine to help with the housework and it coming to life when fed horrible sweets, the show did have the right ingredients to make it a success with its target audience. Writing each of the 41 episodes was Colin Bostock Smith, who’s impressive cv includes contributions to such shows as The Two Ronnies, Terry and June, Shelley and Not the Nine O’Clock News. Producing and directing the series was ex-Monkee Micky Dolenz.

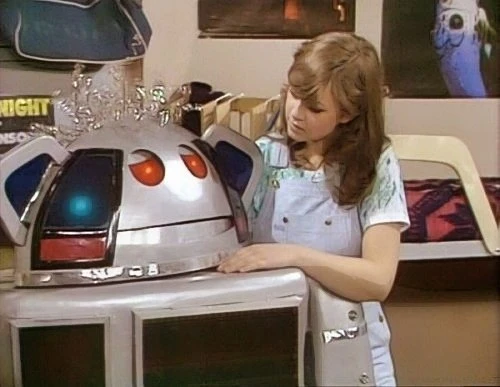

Mickey is being designed by boy genius Ken Wilberforce in order to assist his mother with household chores. When we first meet him, Mickey is static and lifeless, and Ken’s initial desire is to simply get him mobile using his remote control. Aside from Ken there is Steve, borderline hooligan and bully, and Haley, studying for her A levels and keen to make the transition from girl to womanhood. The family patriarch is played by Michael Stainton, a building society manager trying to keep his kids acting with some degree of normality. Neighbour Janey is around when the three Wilberforce children leave the room, and she finds herself alone with Mickey and a packet of ghastly sweets – galactic fizzbombs – for company. She pops one into Mickey’s mouth and within seconds, the robot’s red eyes glow and he asks for another. Mickey later reveals that the tartaric acid was the key ingredient in bringing him to life. Mickey is only allowed to stay at the Wilberforce home by proving his usefulness by tidying the bedrooms up, something the kids don’t want to do and the mother seems incapable of doing.

Mickey himself is a bit of an odd combination. Imagine a mechanised version of Mr Blobby, but with a greater vocabulary and a mischievous nature. He becomes a little like Mork from Mork and Mindy. He has his nicknames for all the family, and much like Mork with Granny, his favourite is the family grandmother whom he refers to as his little fruit bat, and who refers to him as fluffy. Gran offers the largest acting talent in the form of Irene Handl and she does add a great deal of charming mischief to the show. Mickey is of course intent on looking out for his new family, and the humour is balance with heart, although the comedy is at times quite Blackpool postcard with Mickey’s approach to the ladies.

Mickey himself was controlled by his creator John Edwards, who stoically refused to take direction personally, only if it was addressed to Mickey himself. Whether Metal Mickeycan fully be classed as television heaven will be mainly down to personal viewpoints. There are plenty of people whose recollections are that the robot himself was just too two-dimensional and difficult to understand to properly appeal. But the reality is that the robot was a big success, the show lasting 41 episodes, attracting up to 12 million viewers in its Saturday teatime slot and of course spawning the obligatory novelty singles, five in all. Mickey guest appeared on Tiswas and Russ Abbott, the whole cast recorded an album, and even after the show went off the air Mickey continued for several years in magazines and comic annuals. Love him or loathe him, Metal Mickey commanded healthy viewing figures, entertained kids after World of Sport had concluded and provided plenty of easy Christmas presents for kids of the early 1980s – and in that respect, Mickey deserves his place in Television Heaven.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 7th, 2020. Written by Brian Slade for Television Heaven.