The Tudors

2007 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

Historical drama and fiction can be divided into two main categories: the Romance, in which great historical events are the background to the main story; and the Epic, in which the great historical events are the main story.

It is understood that the Romance is not history and so it is allowed to take some liberties with facts. However, the public rather expects that the Epic is basically historical, and producers do not always respect this as they ought.

Epic can therefore be subdivided further according to the degree of respect paid to its source material. The highest form attempts a fairly honest retelling of the facts - in television terms, the likes of The Caesars, Elizabeth R, and Fall of Eagles. Next in status are those that stick to accepted primary sources but which tend, for justifiable dramatic purposes, to give undue weight to the more scandalous, less reliable historical material - I, Claudius, Napoleon and Love, The Devil's Crown, and the BBC version of The Borgias.

Much lower down the scale are those which take the main characters and the basic situation from history, and perhaps some of the more famous or dramatic events, and then use them to make up their own stories - Spartacus: Blood and Sand, Vikings, Versailles, and the Neil Jordan version of The Borgias.

In many ways, The Tudors was the beginning of the recent general slide from the former categories towards the latter. There were historically inaccurate historical dramas before but for the most part they were clearly in the Romance category. The major innovation of The Tudors was to make a Romance out of the great events of history themselves that were supposed to be the stuff of Epic. Boundaries have been blurred to the point of invisibility.

The central figure in this revolution is Michael Hirst, executive producer and writer of The Tudors. These days he happens to be executive producer and writer of Vikings, and after The Tudors was a producer for the Neil Jordan version of The Borgias. In between, he was executive producer of Camelot for Starz, who were responsible for Spartacus: Blood and Sand around the same time. Prior to making The Tudors, he wrote the feature film Elizabeth for Shekhar Kapur, and later its sequel Elizabeth: the Golden Age. Both films were roundly condemned for their historical inaccuracies. In particular, even to those like this reviewer who are not Roman Catholics, there are unpleasant traces of the Anti-Catholic "Black Legend."

Hirst therefore seems to have been present at all the crucial moments and places in this new trend of blurring fact and fiction in historical drama. If one man deserves the credit or the blame for it becoming the fashion, it is him.

In fairness, Hirst's writing is usually well researched, and so are his productions when it comes to sets, props, costumes, and period detail in general. It is simply that he seems to feel no obligation to stick to historical facts when they get in the way of his fictional narrative.

In this he is doing no more than following an established Hollywood tradition. In historical drama, the drama has always come first and the history a poor second. Just look at Shakespeare. What has changed is the level of historical inaccuracies in the sort of production audiences used to assume was basically accurate.

People in "the industry" say this does not matter because they are only entertainers. This is disingenuous. Film and television have enormous potential for political manipulation. Some political activists are open about trying to manipulate it. At a time when assumptions about history influence how people vote, and those assumptions are more likely to be based on popular entertainment than serious research, mainstream producers are under an obligation to be responsible.

Anyway, the point here is that The Tudorsis very, very inaccurate - but also something of a guilty pleasure. Say what you like about Hirst, he really is an entertainer.

The casting of Jonathan Rhys Meyers in the lead makes the very good, and historically valid, point that, contrary to the popular image today that is based on his increasingly self-indulgent later years, the young Henry VIII was generally considered to be exceptionally virile and handsome by his contemporaries. Other than that, his performance has little in common with the historical Henry. However, a late shot of him eating and beginning to turn into the more familiar Henry is very well done, as is a scene in which an ageing Henry curates his own public image using the famous Holbein portrait. The real Henry seems to have had a very modern grasp of the power of brand.

Overall, the project was sold on the basis that it made the Tudors in general and Henry in particular more "sexy." There are certainly a lot of prurient scenes that seem aimed at the all-important demographic of young males. All too often it seems like "Tudors for Teenagers."

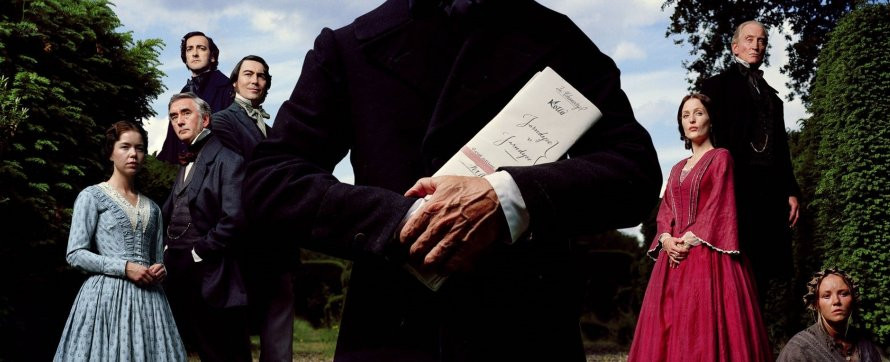

Three compelling supporting performances are all that stand between the more discerning viewer and giving up in disgust at the gratuitous sex and general contempt for history.

The first, predictably, is Sam Neill as Cardinal Wolsey. Neill is one of those actors who always earns his pay, and here he carries the whole first season on his own, playing one of the great unsung heroes of British history. Wolsey, a self made man, a champion of the poor, and one of the most accomplished statesmen his country ever produced, deserves a better public image, and Neill gives it to him. Although he looks nothing like the historical Wolsey, he conveys his energy, his ambition, and his ruthless intelligence with such credibility that one can imagine just how the real Cardinal came across. The point is well made that this was a political operator feared and respected all over Europe. Only an anti-historical suicide strikes a false note: it would have been totally out of character for the real Thomas Wolsey.

With him gone, there was a strong temptation to stop watching, but the baton was picked up by the young Natalie Dormer in her breakthrough role as Anne Boleyn. History is becoming more sympathetic towards Anne and Dormer's incredibly assured performance reflects that, but without sugarcoating her calculating ambition. The tense scenes leading up to her delayed execution are incredibly moving.

With her gone in her turn, it seemed like finally time to give up on the whole tawdry show, but then someone else picked up the baton - perhaps the most surprising person of all. Henry Cavill, also in his breakthrough role, as Henry's best friend, Charles Brandon, First Duke of Suffolk, seemed at first no more than another bit of beefcake. However, as the series goes on, both the character and the actor appear to mature. There is one particularly poignant scene in which Suffolk, wealthy and in the King's favour, begins to wonder about the morality of some of the things he has done for Henry to get there.

After that it was no surprise that both Dormer and Cavill went on to higher things.

It is in general a very strong cast, including big names like Max von Sydow and Peter O'Toole turning up for the cheque in cameos. There is a strong Irish contingent, which is not surprising since principal filming was in Ireland. Maria Doyle Kennedy stands out as a particularly convincing Catherine of Aragon. One can understand how this was a woman whom Henry once loved sincerely and passionately. It is harder to understand why he left her.

Irish locations stood in fairly effectively for their English equivalents, and Hirst's experience there led him to use Ireland as his production base for his later Vikings.

The production values in general are commendable, and the result is colourful and very easy on the eye. The historical Tudors spent huge sums in historical display, and in this the production seems to have followed in their tradition.

If one sometimes feels that more effort has gone into ensuring that serious historical research is reflected in the details of costumes than in the script, that is a fair criticism of nearly all historical drama, even before Michael Hirst.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 23rd, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.