Then There Were Giants

1994 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

Originally World War II: When Lions Roared, this two part miniseries was released in non-American Anglophone markets as Then There Were Giants, an even more uninformative title that invites confusion with the poignant feature film They Might Be Giants, with which it has absolutely nothing in common.

For anyone interested in what it is actually about, Then There Were Giants is a dramatisation of the prickly relationship between Winston Churchill, Josef Stalin, and Franklin D Roosevelt during the Second World War. It was apparently based on a planned twelve hour (!) stage play, and is therefore unusually talky and stagy for as a major US network show - and all the better for it.

It operates on two levels simultaneously, as a relationship drama and as a political drama, with the personal obviously impacting on the political and vice versa. Churchill and FDR were men of similar backgrounds and attitudes. Both were aristocrats, even if Churchill had more cachet and Roosevelt more cash. As such, both were essentially conservatives but with strong streaks of both paternalism and pragmatism. Stalin, a socialist and, unusually among the Bolshevik leaders, genuinely working class, was initially the odd man out, having little in common with the other two. The main storyline in the relationship drama is Stalin's successful seduction of FDR, detaching him from Churchill, who was left isolated - a sort of "love triangle" except without any love.

The word seduction is, of course, used in a strictly political sense, and is actually based on an analogy made by Churchill himself, who did not allow what seems to have been a genuine affection for Roosevelt blind him to the practical necessity of doing whatever it took to keep the American President happy.

From the moment he became Prime Minister Churchill was fully aware of how American finance, industry, and, eventually, manpower were crucial to any hope of beating Hitler. American public opinion, while more sympathetic to Britain than to Germany at that point, did not want to get involved in what most Americans then saw as yet another pointless European war. Roosevelt owed his re-election to an unprecedented third term as President in 1940 largely to the perception that his experience made him the man most likely to keep America out of it, which he promised to do. The Democrats in particular were hostile to the British Empire and did not want to do anything that might be seen as underwriting it. FDR himself shared this attitude, even if, unlike many his Administration, he seems to have realised that the end of the British and European Empires would leave a vacuum America would have to fill. Churchill, by contrast, was an old Imperialist romantic who, almost alone among leading British statesmen by this stage, saw the Empire continuing to play a major role long after the War.

This was the crack in the original "Special Relationship" that was papered over in all the propaganda about Anglo-American friendship that remains influential to this day - and that Stalin was able to exploit. Churchill saw the ruthless revolutionary for what he was, but FDR seems to have viewed Stalin as something like the sort of Left winger he knew exactly how to handle in his own party. It was a fatal error, especially for the peoples of Eastern Europe.

The three men differed on how to fight the War and what would happen afterwards. Stalin was so desperate for an Anglo-American landing in France as early as 1942 to take the pressure off Russia that he ignored how impractical such an offensive would be at that point. Contrary to the impression of the inevitability of success that comes with hindsight, D-Day was a very risky proposition even in 1944 and a messy failure would have had a profound effect on American public opinion: America would probably have stayed in the War but it would have reopened an earlier debate, not shown in Then There Were Giants, which Churchill and his military advisers had won, to give the European Theatre priority over the Pacific. Churchill was therefore walking a tightrope, trying to keep the American focus on beating Hitler but away from a direct assault on France for which he knew the Americans were not ready. As in the First World War, the American high command were essentially clueless to the extent that they did not even know how clueless they were, thinking they knew everything and that they were in a position to teach the war hardened British how to fight.

Churchill won the battle to delay D-Day until the Americans were over in strength, fully prepared, and more experienced in fighting the Germans (a fine "television movie" with Tom Selleck, Ike: Countdown to D-Day, makes the point well that it was still a close run thing). However, Britain became less important to America after that and Churchill was to a great extent sidelined in favour of Stalin by FDR. The result was the Cold War.

Most of this is conveyed accurately in Then There Were Giants. There are, however, some errors, most notably when FDR is shown as upset at suddenly finding America at war in 1941: while Pearl Harbor was an unpleasant tactical surprise, FDR had in fact been preparing America for war diplomatically and militarily ever since his re-election on that promise to stay out of it. There are also some strange omissions, most notably the fact that Churchill and FDR had been in effect "pen pals," maintaining a very friendly correspondence, since 1939, and Stalin's success in charming even Churchill at their first bilateral meeting before later dropping him in favour of FDR.

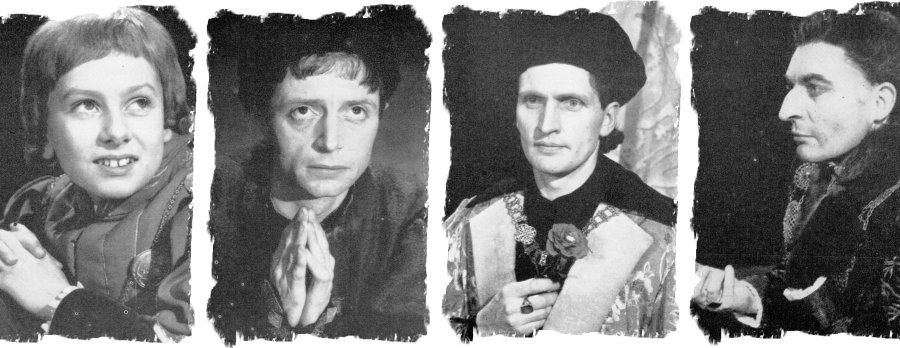

It is a stripped down production with heavy reliance on old newsreels, few sets, little location filming, and only five speaking parts plus a "voice over." All the money seems to have gone on a highly prestigious cast: Sir Michael Caine as Stalin, his frequent collaborator Bob Hoskins as Churchill, and John Lithgow as FDR.

All three excel in roles for which they do not seem obvious choices, Hoskins in particular apparently morphing into a familiar historical figure with whom, superficially, he has little in common. Lithgow exudes the affability that made FDR unusually beloved for a politician, while Caine is at his best when Stalin is at first stunned by the initial speed of the German advances into Russia in 1941 and later when conveying a quiet menace as he gradually takes control of the whole situation. This is how it was.

Incidentally, Lithgow later played Churchill himself, but not so well, in The Crown, and Caine later formed a great double act, in the wonderful Secondhand Lions, with Robert Duvall, who was also a notable Stalin in an earlier television miniseries of that name, reviewed here previously. While both Caine and Duvall are credible Stalins, both are handicapped by being taller than the original, Caine even more so, having a good nine inches on the Georgian megalomaniac.

Ed Begley Jr (St. Elsewhere) plays FDR's "fixer" Harry Hopkins and the versatile Czech actor Jan Triska plays Molotov, Stalin's Foreign Minister. Churchill is not given an equivalent at whom he can throw exposition, so he seems to talk to the camera, which seems to make him the character with whom we are meant to sympathise. As a Hollywood production, the script takes a pro-FDR line, but in the end it is honest about his naivety regarding Stalin and Churchill being basically right. Although the use of split screen to turn long distance correspondence into conversation is distracting at first, one gets used to it. Overall your reviewer was left wishing they had made the full twelve hour version with the same actors, but unsure whether this is a criticism of its superficiality or a compliment - perhaps a bit of both. Certainly the cast and the true life story have the dramatic power to make it an easy watch at whatever length.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 19th, 2025. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.