Hanna-Barbera

by Brian Slade

To an entire generation, British television offered some fairly healthy home produced shows that helped define their childhood. On the BBC, Blue Peter was the jewel in the crown, with a supporting cast of such classics as Swap Shop, Animal Magic, Record Breakers and Crackerjack, while over on the ITV regions, the more rebellious shows like Magpie and Tiswas resided. For younger viewers the staple diet seemed to primarily focus on stop motion puppetry in Bagpuss, The Clangers and the Trumptonshire offerings. British-made cartoon animation was in short supply, with both channels relying on imported shows from America due to the large cost in making such programmes.

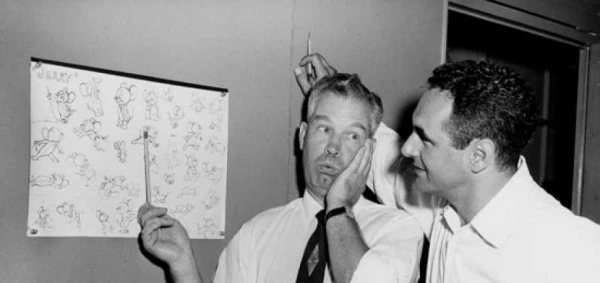

The bulk of imported shows were iconic as they collectively spawned from the minds of a pair of creative geniuses who revolutionised animation and entertained millions around the world. William Hanna and Joseph Barbera took animation to the highest standards in theatres, and when their worlds came crashing down, proceeded to reinvent the medium for the small screen with unparalleled success.

The pairing of Hanna and Barbera was not one that originated from a pair of youths dreaming of making it big together. Their formative years were miles away from one another. Born in 1911 in New York, Joseph Barbera toiled away at a job in banking during the Depression. A devoted theatre goer from childhood, he wanted to be in entertainment and the talent he possessed to draw saw him continually submit cartoons to magazines. Once a few sold, he took a job at Max Fleischer’s studios, but despite the company producing Popeye and Betty Boop, Barbera felt there was limited opportunity to make a living and so tried to return to his banking job…only to find his job was no longer available. As luck would have it, a friend recommended he try for a job at the Van Beuren Studio, also in Manhattan. Five years into his new vocation however, the company went out of business, and Barbera was once again out of work. A chance conversation changed the direction of his life. Having effectively decided that Disney and California were the only options to pursue, Barbera was offered a job at Paul Terry’s studio in New Rochelle.

Meanwhile, William Hanna, born in 1910, was on a course to become a structural engineer until he joined Harman-Ising Studios in 1929. The company was a newly formed one from a pair of ex-Disney employees who produced the first Looney Tunes cartoons. Owner Leon Schlesinger parted ways with Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising, but Hanna stayed loyal to the pair, another pivotal moment in the history of animation. In 1937, MGM decided to create their own cartoon studio, and head Fred Quimby went on the hunt for talent. William Hanna and Joseph Barbera were among those who joined the new studio.

It was with MGM that Hanna and Barbera became a team. Barbera was an expert animator, Hanna an expert in comedy and business. It was these two minds that combined to create the phenomenon of Tom and Jerry. The quality of artistry, the expert comic timing in each of the cartoons, the musical accompaniment and the pace of these cartoons sent the cat and mouse team to stardom, achieving multiple academy awards. Then in 1957, having achieved so much with the pair, MGM pulled the rug from under them by closing its animation studio. Everybody was let go, and the best of the Tom and Jerry cartoons came to an end – as it seemed would the Hanna Barbera team.

Months later, William and Joe began down the road ofrevolutionising the industry that had just dealt them such a brutal blow. It was generally accepted that the cost of producing the kind of animation that had elevated Tom and Jerry to such lofty heights was far too high for any television company to tolerate. Hanna and Barbera knew this too, but rather than try and find work in another company they decided to try and start their own animation studios with the intention of slashing the costs in order to get their cartoons on television.

Their style ruffled feathers then as it did for many years to come. The detailed backgrounds and elaborate movements that typified their Tom and Jerry efforts would be axed. Instead, the style adopted at the Hanna-Barbera Productions studio would be one known as limited animation. A look at any of their successful shows will see the same backgrounds re-used in scenes, minimising the amount of new drawings needed on screen. Similarly, only the necessary segments of the characters would be redrawn. Most crucially, it reduced the costs extensively.

Despite being refused by many, their first effort was comparatively successful. Although rarely recalled by British audiences, Ruff and Ready was a five-minute-long effort using the new techniques and the titular pair were a cat and dog team of opposing intellects. The cartoons made a breakthrough in America, neatly encasing reruns of theatrical animation classics. But as it became clear that there was an audience for new original material, NBC approved a wider range of new series. As Hanna and Barbera began expanding and bringing in established vocal and animation talent, they were given full half hour slots to fill with new material and such future successes as Huckleberry Hound, Pixie and Dixie and Yogi Bear were born.

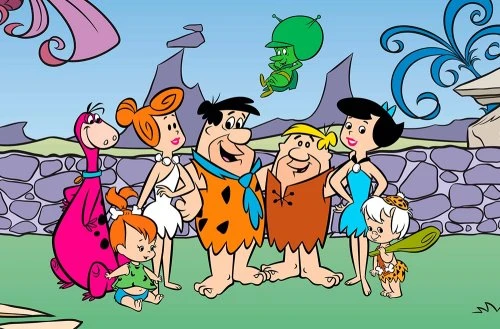

The snowballing of their success continued. Yogi’s adventures stealing picnic baskets from visitors to Jellystone Park, always morally questioned by faithful diminutive pal Boo Boo, led to Yogi being taken into his own half hour slots, along with the creation of further characters. But in 1960, with so much success under their belts, Hanna and Barbera were asked if they could break even more new ground – create a full half hour show with one storyline along the lines of a sitcom that could not only keep the young ones entertained, but draw in a chunk of the primetime adult audiences. So it was that The Flintstones were born.

Based on Jackie Gleeson’s The Honeymooners, The Flintsones followed all the standard approaches of safe family sitcoms. Two pals who worked together and socialised together, with one invariably coming up with questionable schemes to improve his financial status, or indeed his bowling score. Fred and Barney were married to Wilma and Betty and their domestic lives formed the basis of the show. Nothing spectacular, except of course that their modern day problems actually occur in prehistoric times, but the shows were so well written by an ever-expanding team that this simple format won an audience that kept the prehistoric families on screen for decades in spin-offs, reruns and remakes, both animated and live action. Generations of fans on both sides of the Atlantic amused themselves at the various 20 th century gadgets reimagined for the days of the dinosaur. And of course, like so many sitcoms The Flintstones managed to have a catchy theme song and some catchphrases – most notably Fred’s delirious cry of Yabba-dabba-doo!

The success of The Flintstones spawned countless further programmes that entertained generations. Next came The Jetsons, followed by the scheming alleyway cats reporting to Top Cat in a glorious tribute to the shows of Phil Silvers. Touche Turtle, Magilla Gorilla , Secret Squirrel– there were seemingly no animals that couldn’t be brought into the money-making machine that Hanna Barbera had become. And when the animals weren’t involved, villains could be called upon in great number. Wacky Races appeared in 1965, introducing the world to Dick Dastardly and Muttley. In traditional style, the evil pair rarely triumphed against the bizarre cast of misfits competing alongside them. The show itself was yet another glorious success, and Dastardly and Muttley would get their own series, as would Penelope Pitstop.

Perhaps the jewel in the crown of the Hanna Barbera studio came in 1969. The concept of a group of mystery solving teenagers was brought to the company. CBS didn’t like their interpretation, considering it inappropriate for its timeslot and so some quick thinking by daytime head Fred Silverman, with a little help from Frank Sinatra’s Strangers in the Night, allowed them to rework the show. The bit part of the Great Dane accompanying the gang would be elevated to the titular character – Scooby-Doo. Any concerns over the mystery segments were vanquished by the slapstick antics of Scooby, who along with best pal in the gang Shaggy, formed a slapstick double act that ensured that not only Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? became a success, but it would remain popular for the next half a century.

To list the further successes of the studios would be the equivalent of documenting a stockroom of a large supermarket. Suffice to say that generations of children grew up having their own favourite. Help! It’s The Hair Bear Bunch!, Wait Till Your Father Gets Home, Hong Kong Phooey , Captain Caveman – children of the 1970s had an array of characters that they adored as they grew up, even getting a wonderfully indulgent merging of the worlds when they all came together in Scooby-Doo’s All-Star Laff-a-lympics.

In the UK, the shows were priceless to programme planners. Sometimes they held their own early evening primetime slot, sometimes a school holidays regular in the midweek mornings before Why Don’t You… and of course they were perfect for buying programme makers time during the Saturday Morning spectaculars like Swap Shop and Saturday Superstore.

When watching cartoons as a child of the 60s, 70s and 80s, there were very few areas where Hanna and Barbera’s influence wasn’t felt. There were of course some other successes to be seen. Looney Tunes, Mr Magoo and more racy superheroes cartoons, itself a genre that Hanna Barbera succeeded at as well, were frequently seen, but they never wormed their way into audiences’ hearts the way Scooby, Yogi, Fred, T.C. and the plethora of memorable characters managed.

It is somewhat ironic that William Hanna and Joseph Barbera revolutionised animation in the way that they did. Known for the fine details, glorious soundtracks, hysterical gags and brisk pace of their early productions, there wasn’t a Tom and Jerry fan in the land who didn’t heave a sigh of disappointment when after the opening theme it became clear that the cat and mouse duo episode about to be shown was of the later era long after Bill and Jo had departed from MGM. And yet it was this swift, economical animation that the pair determined to make profitable and that eventually allowed television to not only risk but subsequently embrace and rely on the genre.

The pair continued working long after they sold their production studios, remaining at the head of the company into their eighties. For everything that Walt Disney achieved in the movie theatres, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera did the equivalent on television. To generations of children, Hanna and Barbera really were the cartoon kings.

Published on September 3rd, 2020. Written by Brian Slade for Television Heaven.