Jimmy Edwards

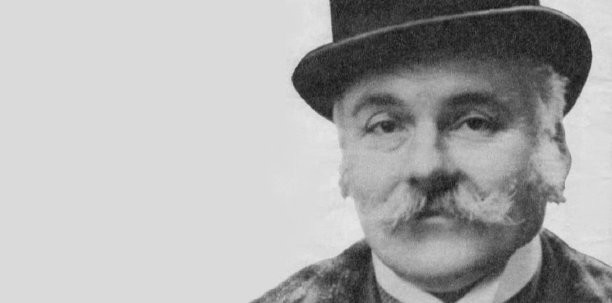

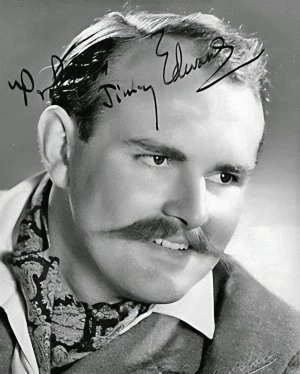

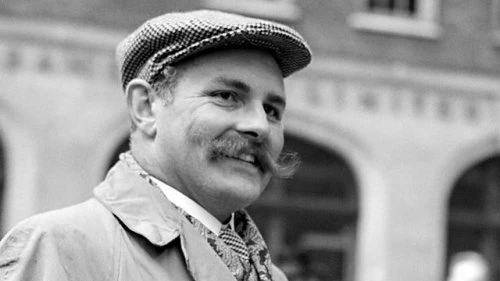

Jimmy Edwards was a larger-than-life figure in every sense; booming voice, trademark handlebar moustache, and a comic timing that made him a household name in post-war Britain. Best known for his television role as the blustering headmaster in Whack-O!, or Pa Glum on the radio, Jimmy carved out a distinctive place in British entertainment history. But behind the bombastic public persona was a man of surprising complexity: a decorated war hero, a Cambridge scholar, a skilled pilot, and a devoted friend. This is the story of a performer who, with a mixture of bravado and vulnerability, made the nation laugh while carrying scars, both visible and hidden, from a life touched by war, fame, and personal struggle.

James Keith O'Neill Edwards was born on 23 March 1920 in Barnes, Surrey, the eighth of nine children and the youngest of five sons. His father, Reginald Walter Kenrick Edwards, was a mathematics lecturer at King's College London, and his mother, Phyllis Katherine Cowan, was originally from New Zealand. The family's circumstances changed dramatically in 1935 when his father passed away, plunging them into financial hardship. To help support the family, Jimmy's older brother Alan left school to join the mounted police, while another brother, Hugh, entered the Merchant Navy as a 14-year-old apprentice.

Jimmy began his education at St Paul’s Cathedral School, where he excelled and rose to the position of head boy. Thanks to a scholarship, Jimmy went on to study at King's College School in Wimbledon before earning a place as a choral scholar at St John's College, Cambridge. There, he read history and sang in the college choir, graduating with a Master of Arts degree. But whatever chosen path he intended, the war would change the course of his life.

During the Second World War, Jimmy served in the Royal Air Force. He later confided to his close friend Eric Sykes that, for the most part, his war experience had been "a doddle." Stationed primarily in Toronto, Canada, he spent much of his time flying Dakota aircraft, training navigators who would plot their courses and direct him back to the airfield.

His relatively easy wartime routine ended abruptly when he was reassigned to England and thrust into active combat. The reality of war hit hard in 1944 during a mission over Arnhem, where Jimmy was tasked with towing a glider into enemy territory. As he and a formation of Dakotas approached their objective, they were attacked by enemy aircraft. The gliders were released quickly, but Jimmy’s plane was struck several times and caught fire.

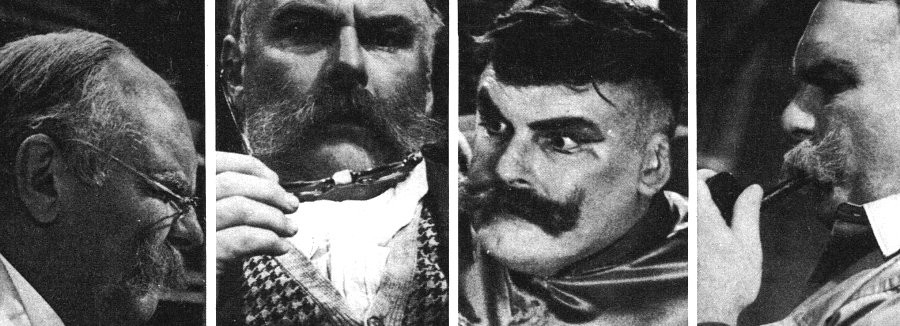

Despite the danger, he managed to evacuate his crew but waited too long to bail out himself. With flames engulfing the aircraft, he somehow succeeded in landing the burning Dakota. He escaped with his flying suit charred and one ear burned away, bracing himself to be taken prisoner by German forces. Instead, he was rescued by the Dutch Resistance and taken to a hospital in the Netherlands. His facial injuries required plastic surgery that he later disguised with the large handlebar moustache that would become his trademark. By the time he had recovered and was declared fit for duty, the war had ended. For his actions and bravery that day he was awarded the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross).

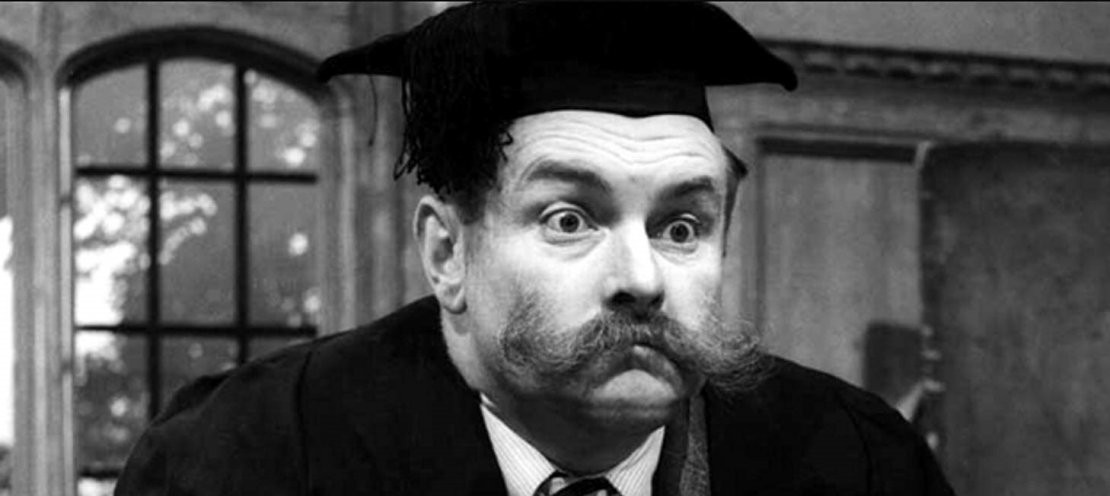

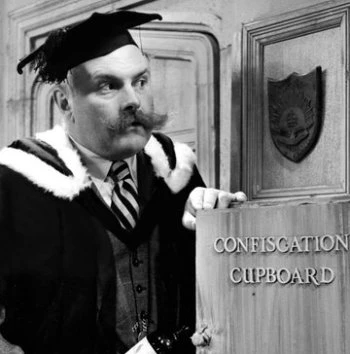

While stationed in Canada, Jimmy had taken part in a number of entertainment shows for airfield personnel. It was during these performances that he discovered his natural gift for comedy and realised that his future, once peace returned, lay on the stage. His first professional appearance after he was demobbed came at London’s legendary Windmill Theatre, where he performed a variety act under the name "Professor Jimmy Edwards."

His early act, a lively mix of academic parody and slapstick, was memorably described by fellow comedian Roy Hudd as "a mixture of university lecture, RAF slang, the playing of various loud wind instruments and old-fashioned attack."

Like many post-war comedians, Jimmy soon transitioned to BBC radio. Frank Muir, who had been writing material for Jimmy during his Windmill Theatre days, developed scripts for a radio character, a disreputable, bombastic public school headmaster. Meanwhile, Denis Norden, also a comedy sketch writer, had been creating material for Australian comedian Dick Bentley. Radio producer Charles Maxwell had already brought together Jimmy, Bentley, and Joy Nichols for the final series of Navy Mixture in 1947, with Muir contributing some of the writing. Following the show's conclusion, Maxwell was commissioned to produce a new weekly comedy series starring the same trio. To shape its content, he introduced Muir to Norden and asked them to collaborate on the scripts.

The series, which began in 1948, was the long running Take It From Here, and five years later, on 12 November 1953, a single sketch proved so popular that Muir and Norden knew they had struck gold. With a few tweaks to the characters, the sketch evolved into The Glums, a recurring segment that quickly became a staple of the programme. The stories followed the misadventures of Ron, the dim-witted son of Mr Glum (played by Dick Bentley), and Eth, his plain but hopeful fiancée (played by June Whitfield), who saw Ron as her only hope for marriage. Ironically, Bentley, cast as the son, was nearly thirteen years older than Jimmy, who played the father. The Glums were remembered sufficiently for the format to be revived in 1978 as part of Bruce Forsyth's Big Night programme.

In 1956, the drunken, gambling, devious, cane-swishing headmaster who tyrannised staff and children at Chiselbury public school in Whack-O! also written by Muir and Norden, cemented Jimmy’s place in television history and made him a household name.

In 1960, Whack-O! was adapted into a feature film titled Bottoms Up, with a screenplay by Michael Pertwee and additional dialogue provided by Muir and Norden. On television, Jimmy continued to build on his comedic success with a trio of sketch-based series: The Seven Faces of Jim, Six More Faces of Jim, and More Faces of Jim, which also starred a young Ronnie Barker, showcasing both men's versatility in a range of comic roles.

On stage he appeared in the London Laughs revue with Tony Hancock and Vera Lynn, he played the King in Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella at the London Coliseum with Kenneth Williams and Tommy Steele and travelled to the other side of the world to play at the last night of Melbourne's Tivoli Theatre.

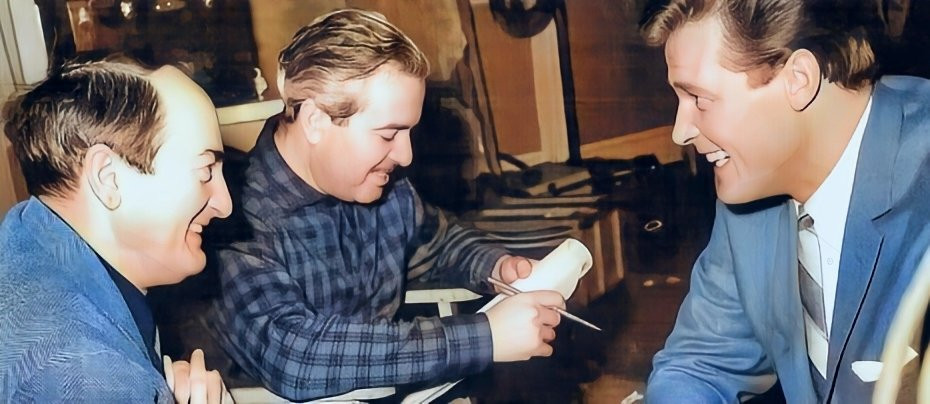

In 1967, Jimmy rang Eric Sykes with a proposition. Jimmy had been approached by the impresario Michael Codron to appear in a six-week tour of a comedy show which would end up on the London stage. Jimmy told him he'd only do it if Eric would. Sykes readily agreed and asked Jimmy what the show was about. "No Idea," he replied. "I haven't read it yet."

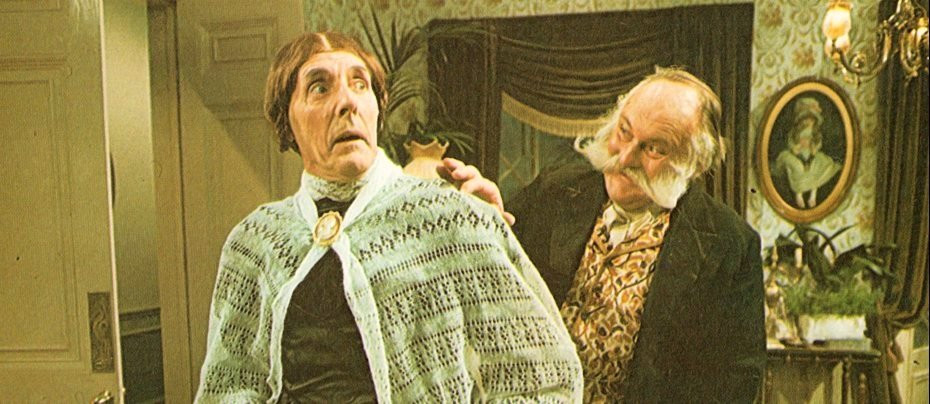

The first week of the play, Big Bad Mouse, was a complete disaster. According to Eric Sykes, the second week was even worse! The critics hated it and the audiences stayed away to the point where the cast outnumbered them. By the fifth week it was clear that there was no way the play was going to go to London and so for the sixth week Jimmy decided to have 'a bit of fun' with it. He told Eric that he intended to ad-lib all the way through the play, largely ignoring the script. Eric agreed to play along.

On the first night of the last week of the provincial tour, at the Palace Theatre, Manchester, the two stars put their plan into action, and it literally brought the house down. Frankie Howerd, who was in the audience that night told them it was the funniest thing he'd ever seen. By the third night the public couldn't get tickets for it because each house was sold out. Over the course of the week, over a thousand people were turned away from the box office and even Michael Codron, arriving on the last night, couldn't get into the theatre. The show did reach London, at the Shaftsbury Theatre and over the next twenty years or so Jimmy and Eric toured the world with it (with Roy Castle sometimes replacing Sykes) and the play earned the monicker ‘the most successful flop in theatre history.’

Back on television, Jimmy starred in The Fossett Saga in 1969 as James Fossett, an ambitious Victorian writer of penny dreadfuls, with Sam Kydd playing Herbert Quince, his unpaid manservant, and June Whitfield playing music-hall singer Millie Goswick.

In his private life, Jimmy Edwards was a lifelong Conservative and stood as the party’s candidate for Paddington North in the 1964 general election, though he was ultimately unsuccessful. His candidacy attracted widespread media attention, much of it mocking, though the local party maintained that they had selected “Jimmy Edwards the man,” not the comedian. Taking the defeat in good humour, Jimmy later styled himself with characteristic wit as “Professor James Edwards, MA, Cantab, Failed MP.”

Jimmy was married to Valerie Seymour for 11 years, from 1958 to 1969. A decade later, in 1979, he was publicly outed as gay, an unwelcome revelation for him at the time. Following the end of his marriage, there were press reports suggesting an engagement to actress, singer, and comedian Joan Turner, though many suspected this to be a mutually beneficial publicity stunt. In a 2015 UK-Gold documentary, Frankie Howerd: The Lost Tapes, fellow comedian Barry Cryer named Jimmy among several post-war performers who had been compelled to hide their sexuality due to the societal attitudes of the time. Jimmy spent his later years in Fletching, East Sussex, and died of pneumonia in London on 7 July 1988, at the age of 68.

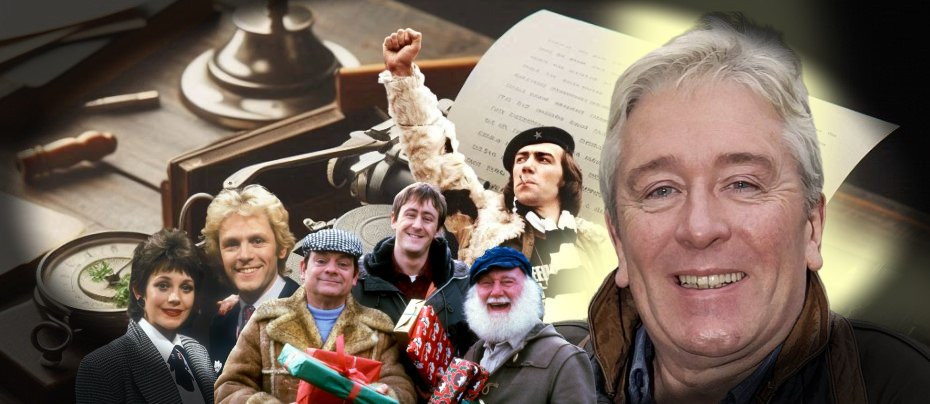

Jimmy Edwards holds a distinctive and well-earned place in the pantheon of British comedy performers - a bridge between the boisterous music hall tradition and the more scripted, character-driven comedy that defined post-war radio and television. Alongside contemporaries like Frankie Howerd, Tony Hancock, and Kenneth Horne, Jimmy helped shape the golden age of British radio comedy.

Unlike some of his peers, Jimmy brought a uniquely patrician air to his comedy, blending Oxbridge wit, RAF bravado, and an old-school theatricality that set him apart. He embodied a very British type of absurdity: authoritative, ridiculous, and self-deprecating all at once.

Though his name may not be as instantly recognisable to later generations, within the lineage of British comedy, Jimmy Edwards remains a foundational figure, part of the scaffolding on which modern British humour was built. His influence, especially in the crafting of comic personas and the use of satire to lampoon authority, can still be felt in generations of performers who followed.

Published on September 15th, 2025. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.