Captain James Cook

1986 - Australia‘Since Cook was one of the Heroes of the British Empire, it is only to be expected that he has now become the poster boy for the alleged sins of British colonialism in the Pacific’

Captain James Cook review by John Winterson Richards

Once unquestionably on every list of "Great Britons," Captain James Cook is one of the most remarkable people in history. A self-made man born into humble circumstances; he rose through the ranks of an extremely class-conscious culture to lead three epic voyages of discovery that literally changed the way the world looked at itself. In the process, the expeditions made original contributions to geography, astronomy, navigation, anthropology, botany, and zoology, that secured Cook, a man of limited formal education, election as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Since Captain James Cook, a prestigious Australian miniseries with Keith Michell in the title role, was shown around the same time as the first episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation, it was impossible not to think of the obvious parallels between Cook and Jean-Luc Picard of the fictional Enterprise (it may be amusing to speculate if the Australian Michell playing the Yorkshireman Cook influenced the real-life Yorkshireman Patrick Stewart playing the Frenchman Picard, but, as often happens, the two similarly themed projects were produced at the same time). Like Picard, Cook held a military commission and commanded a warship but was primarily an explorer, a diplomat, and a scientist with a wide range of intellectual interests. Like Picard, Cook made "First Contact" with numerous previously unknown cultures and, contrary to what ignorant revisionists might claim, endeavoured to study them as they were and treat them with respect.

The miniseries was commissioned to tie in with the following year's Australian Bicentenary, at which time there was no serious questioning of Cook's heroic status. Cook did not discover Australia but was the first to map its East Coast accurately, preparing the way for the colonisation that began soon after his death. If there had been no Cook, there would have been no Australia in its current form.

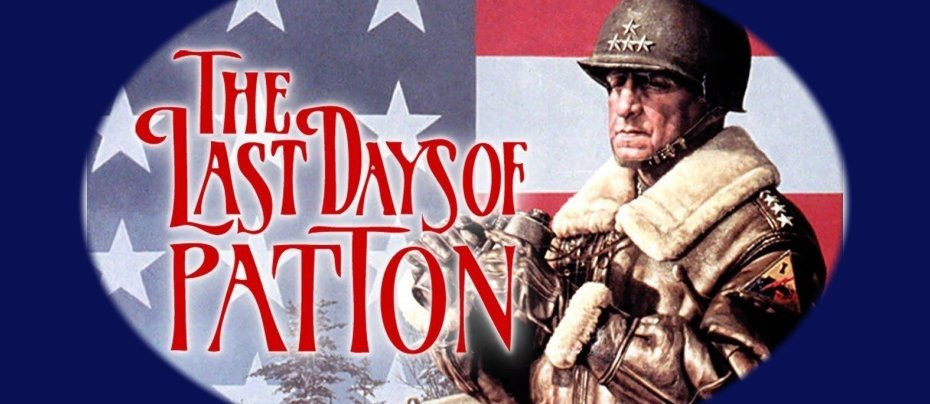

As well as this broader cultural significance for Australia as a whole, Captain James Cook has a particular significance in the history of Australian television. The "Australian New Wave" in cinema was followed in the 1980s by a number of very high-quality miniseries on television, including Anzacs (1985), Vietnam (1987), and Bangkok Hilton (1989). Captain James Cook is an important part of that revolution. A great deal seems to have been spent with the deliberate intention of competing with the very best American historical miniseries such as Shogun (1980) or George Washington (1984).

In this, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation succeeded - in co-production with Revcom France and Norddeutscher Rundfunk, which is further evidence of Cook's global status. A great deal of time and money was spent getting the look of the thing right. The uniforms, set dressings, and props are faultless as far as this son of an antiques dealer could see. The location work is clever and often beautiful, backed by an evocative score. The best decision was hiring the replica of HMS Bounty that had been made for the 1984 feature film The Bounty to play Cook's various vessels. It really is a star.

The whole thing bears comparison with the Australian Peter Weir's later feature film Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, which is itself as perfect a reconstruction of a historical time and place as it may be possible to achieve. If Captain James Cook falls short of that very high standard, it is mainly because some of the details in the dialogue lack the scrupulous attention to detail on the visual side.

This is not to say Peter Yeldham's script is inaccurate. On the contrary, it is a lesson to younger scriptwriters on how to research and how to incorporate the fruits of the research into the story without showing off. Yeldham obviously read Cook's Journals diligently and absorbed a fine sense of the man. He has less of a sense of time and place. Some of the dialogue is too "on the nose," especially for the period. In particular, a man's social status was of far greater importance to every aspect of his life than it is today, but, for that very reason, he would have been far more circumspect about expressing himself on the topic. The novels of Patrick O'Brian, on which the Master and Commander film is based, convey the exquisite subtlety of the social system far more effectively.

Yeldham might argue he had to make the issues clearer to a modern television audience, most of which could not possibly understand the nuances, which is a fair point, but his solecisms still grate because the rest of his script feels so authentic. So do anachronisms like the use of the modern American term "Executive Officer," which is not to be found in Cook's Journals or any other 18th Century British Naval document your reviewer can recall.

The prestige of the project lured one of Australia's greatest actors "home" from the United Kingdom. Michell was one of the last generation of talented Australians who had looked to "The Motherland" for a fulfilled career - one of the things that the "Australian New Wave" was later to change. It had been the right move for him at the time. He flourished on the London stage, becoming one of the most acclaimed Shakespeareans of a talented generation, and the first, arguably the best, Don Quixote in Man of La Mancha on the West End before promotion to Broadway. He became known to a much larger audience in the leading role in The Six Wives of Henry VIII, the epic television series that really established the BBC as the world's most prestigious producer of historical drama for the next decade or so.

However, although its sequel, Elizabeth R, led its star, Glenda Jackson, to a glittering international film career, the same did not happen to Michell for some reason. Perhaps he did not really want it: back then "serious" actors like Michell really did consider the theatre the only place where they could explore characters properly, and film and television were only there for when they had bills to pay. Michell's relatively few screen appearances were nevertheless almost invariably a cut above the rest, especially as Mark Antony in Julius Caesar in the BBC Television Shakespeare and as a Vicar whose faith is challenged when he witnesses an apparently supernatural event in The Miracle, a thoughtful 1985 television play of which your reviewer would dearly love to get a copy to see if it is as good as remembered.

It is therefore fair to say that Captain James Cook offered Michell his most substantial television role since Henry, another historical authority figure, and he seems to have prepared thoroughly for it. If one did not know he was born in Australia, one might have assumed that Michell was as Yorkshire as Cook himself. It is not just a matter of putting on an accent. Michell masters the slightly belligerent stance and attitude traditionally associated with the North Riding (whether fairly or not is not for your reviewer to judge). Once one has seen his performance it is impossible to think of Cook without visualising Michell. It helps that he bears a fairly strong resemblance to the most famous portrait of the great explorer.

Michell had already proved he also knew how to convey command presence. His Cook, like his Henry, is a man of strong passions, but, unlike Henry, he generally keeps them under tight restraint. The historical Cook in his prime projected a calm, controlled, almost stoical demeanour that must have been very reassuring to his crew as they ventured into the unknown and escaped, sometimes narrowly, from several very dangerous situations. Michell is wholly credible in this. He is also honest about Cook's increasing tendency to lose his famous self control on his Third Voyage. The script suggests some of the reasons for this, but it is also probable that Cook's health was declining with age and he may have been more reluctant to take on that final mission than the script implies. All that said, it should be noted the officers who accompanied him on the Third Voyage still looked to Cook as a role model, and several of them became noted explorers and navigators in their own right.

The most recognisable faces in the supporting cast are Carol Drinkwater as Cook's wife and Fernando Rey, odd but effective casting as Lord Hawke, a fighting sailor who rose to become First Lord of the Admiralty. His beard is an anachronism, but no one was ever going to tell Fernando Rey to shave it off. Xabier Elorriaga plays Hawke's successor, the Earl of Sandwich, a man with, let us say, a very broad range of interests - yes, he is that Sandwich - as more Machiavellian than he probably was. Noel Trevarthen looks the part as Sir Hugh Palliser, another blue water seaman who proved a stout supporter of Cook.

John Gregg probably overemphasises the aristocratic playboy in Sir Joseph Banks, in effect Cook's Science Officer on his First Voyage. The French actor Maurice Risch is dubbed with a comedy relief Welsh accent as Surgeon Munkhouse despite the Munkhouse brothers actually coming from Cumberland. Steven Grives excels as an initially very unsympathetic Royal Marine who eventually thrives under Cook's leadership and becomes a loyal friend. David Whitney plays William Bligh cleverly as an overeager young man. Bligh's later voyage to Timor in an open longboat after the Bounty Mutiny is one of the greatest feats of navigation - and leadership - in history and is in large part a tribute to what Bligh obviously learned from Cook.

Overall, the production is accurate and fair to Cook. It would almost certainly not be if it was being made today. The revisionists have become more influential and a working scriptwriter, even if he did his research properly and knew the truth, would come under intense pressure at least to nod politely in their direction.

Since Cook was one of the Heroes of the British Empire, it is only to be expected that he has now become the poster boy for the alleged sins of British colonialism in the Pacific. This is obviously not the place to debate the validity of such allegations. Suffice it to say here that, whatever came after his death, Cook never conquered or colonised anywhere. The explicit purpose of his Voyages was exploration. The places he mapped would have been found by someone sooner or later, and, having been found, their underused natural resources would eventually have been exploited. The records of the various colonial powers suggests that for the indigenous peoples being discovered by Cook, as opposed to any of the only other viable alternatives then on offer, was definitely by far the least worst option.

The more reasonable revisionists therefore confine their accusations to direct violent conflicts between Cook and some of the indigenous people he encountered. These are as they are portrayed in Captain James Cook, even if it must be noted that the miniseries views events from the perspective of its protagonist, based on the Journals kept by Cook himself and his subordinate officers. The indigenous people may have had a different perspective.

For there is no doubt that the clashes were due to cultural misunderstanding, especially about the concept of property. Cook's Journals are clear that violence was absolutely the last thing he wanted. He was confused and exasperated when it broke out. He came to talk and to learn. He made a deliberate effort to cultivate friendly relationships. He negotiated and traded despite having the power to take what he wanted by force. He wanted to find out more about the cultures he encountered and had no desire to impose his own. As a navigator, he was particularly eager to take advantage of the astonishing seafaring traditions of the Polynesian peoples and welcomed those who wanted to join him. It is if anything, quite surprising how much access to his ship he granted to local people, at least on his earlier Voyages: that may, in fact, have been the root of some of his problems and he later felt obliged to change this policy.

Yet he was not naïve. The script might have done more to emphasise that most of the cultures he encountered were definitely not pacifist. The Māori and the Hawaiians in particular had very aggressive warrior traditions - a few decades later Darwin described the former as the most warlike people in the world. When faced with conflict, Cook's philosophy was that a strong display of force was likely to deter greater violence. He was proved right more often than not, and on the occasion when he was proved fatally wrong it could be argued that his mistake was underestimating the threat and not going in with greater strength.

If there are omissions - the miniseries predates Dava Sobel's book on longitude, so it should not surprise that more is not made of Cook's contribution to solving that problem - it is only because Cook achieved so much that it would be impossible to fit it all in. Captain James Cook is nevertheless in general both good history and good drama, and further proof that good history actually makes good drama more dramatic.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 24th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.